Jazz and Deadheads: So Many Roads

A Grateful Dead/Jazz/Jam Brain Dump In Memory of Phil Lesh 1940-2024

There is no tragedy in a life well-lived that runs its course, yet there is loss. —Robert Fripp

Listening for the secret, searching for the sound

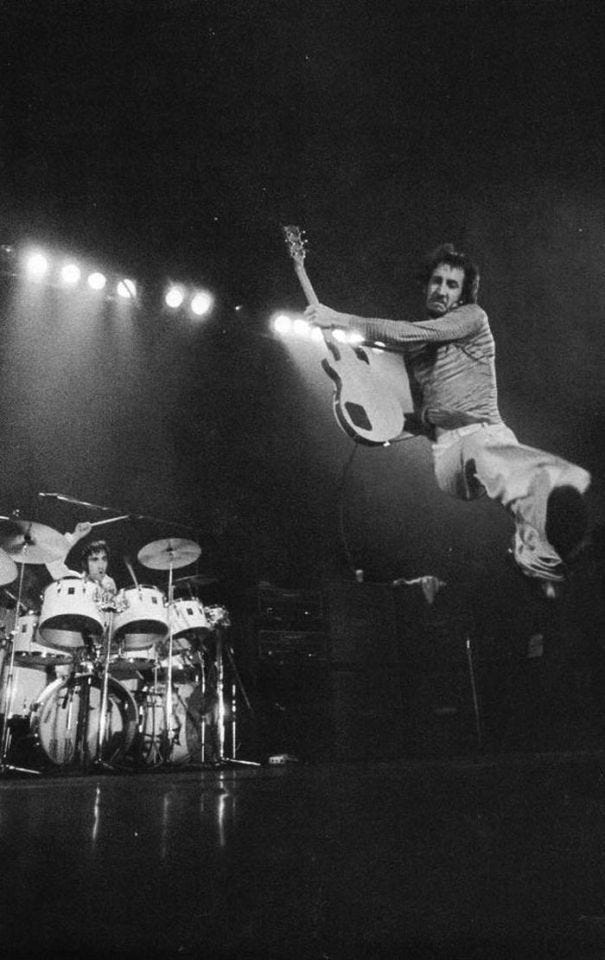

The news that Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh had flown from this world this past Friday wasn’t a shock, but it made me sad. Given Phil’s hepatitis-C diagnosis in 1998, which led to a liver transplant the following year, and subsequent diagnoses of prostate cancer (2006) and bladder cancer (2015), he’d beaten the odds. Still, when a musician I’ve grown up listening to and admiring crosses over, it feels unexpected. Probably because, in my mind, those musicians are still as I saw them in the pages of Crawdaddy or Rolling Stone as a teen. They were larger than life in midflight on stage, rocking out in prime physical condition regardless of extracurricular vices and looking cooler than I’d ever looked on my coolest day ever.

Nobody thinks of their rockstar heroes as illness-ravaged, bedridden shells of their former selves, with IVs delivering pain relief while the inevitable approaches. It’s not only heartbreaking; it’s an uncomfortable reminder of one’s own mortality.

Phil Lesh did a LOT more than beat the odds, though. Phil’s touring, music-making, and charitable works for the past three decades are the efforts of a grateful man whose new liver gave him the chance to do what he loved most—make music. In the wake of Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995 and the dissolution of the Grateful Dead, Phil created a rotating cast of touring musicians called Phil & Friends. They were (IMO) the best of the post-Grateful Dead bands, making music that expanded on the Dead’s innovations instead of simply repeating them. Phil also bridged the generations of OG Fillmore-era acts like the Allman Brothers, Traffic, and The Band with modern jam bands like Phish, Goose, and Widespread Panic. For my hardcore jazz subscribers wondering if they should stop reading now, some of Phil’s other friends to share the stage that lean jazzier have included John Scofield, Greg Osby, Stanley Jordan, Branford Marsalis, Robin Ford, and John Medeski.

Jazz and the Grateful Dead have crossed streams since the beginning, as Dead lead vocalist/rhythm guitarist/composer Bob Weir wrote in his statement following the announcement of Phil’s death:

“At the age of seventeen, I listened to the John Coltrane Quartet, focusing on McCoy Tyner’s work, feeding Coltrane harmonic and rhythmic ideas to springboard off of - and I developed an approach to guitar playing based off of it. This happened because Phil turned me on to the Coltrane Quartet.” —Bob Weir paying tribute to the late Phil Lesh, Oct 26, 2024

Jerry Garica was also open about his love of jazz, noting that he incorporated Miles Davis’s use of space into his playing, commenting, “Nobody plays better holes than Miles, from a musician's point of view” (Rolling Stone, 1974). He also greatly admired John Coltrane’s approach to long-form exploration and improvised storytelling, saying: “an idea that's been very important to me in playing has been the whole 'odyssey' idea - journeys, voyages, and adventures along the way” (Rolling Stone, 1972).

Over the years, the Dead dabbled with jazz, from touring with a horn section in September 1973 (their jazziest year) to inviting iconic jazz musicians to perform with them, such as David Murray, Branford Marsalis, and Ornette Coleman. Garcia returned the favor to Ornette by guesting on his 1988 album Virgin Beauty. I don’t have any sources to confirm that the Dead “borrowed” the idea of setlist song segues from Miles, but the timing is interesting. During Miles’s fall 1967 tour with his Second Great Quintet, he began playing continuous sets, one song segueing seamlessly into the next. The Dead started experimenting with a similar format in early 1968. Coincidence? Maybe.

Once in a While, You Can Get Shown the Light

A willingness to buy into the Dead/jazz argument relies (to some degree) on the listener’s mindset as they play the music of the Dead—are they seeking jazz or finding jazz? This question is one of intention and openness to discovery. Seeking is an active search for something specific or ideal, often accompanied by a preconceived notion of what you’re looking for, and with the hope of encountering something that meets those expectations. This goal-oriented approach can be rewarding, but the outcome is frustration if the answer is elusive. In contrast, finding is often a more spontaneous experience, arising when we’re open and receptive to discovering unanticipated results in unexpected places that satisfy the goal. It requires more mindfulness and less direct pursuit, allowing the answers to reveal themselves in subtle or otherwise overlooked moments. A successful outcome can feel like a surprise or a gift, especially when we see or hear it in something we already know.

So there’s no arbitrary Grateful Dead Jazz-o-Meter. I am not claiming that the Dead were a closeted jazz band or that every Dead show or every era of Grateful Dead music had a hidden jazz agenda. Regarding the Grateful Dead, I hear the jazz spirit of adventure recast through a psychedelic lens and infused with Americana, folk, and bluegrass influences.

If You Get Confused, Listen to the Music Play

A great example is “Playing in the Band.” It’s the fourth most played song in their 2300+ concert history. During its peak performance years of 1972-1974, PITB was one of the Dead’s primary vehicles for improvisation, with many renditions pushing well past the 20-minute mark. While the “head” of the tune (the primary verses and choruses) are essentially identical other than a varying sense of urgency, it’s around the 2:45 mark when the Dead launched into exploratory modal jams that varied wildly, with different influences, vibes, and resolutions.

Let’s take this one from Roosevelt Stadium on August 6, 1974, for instance:

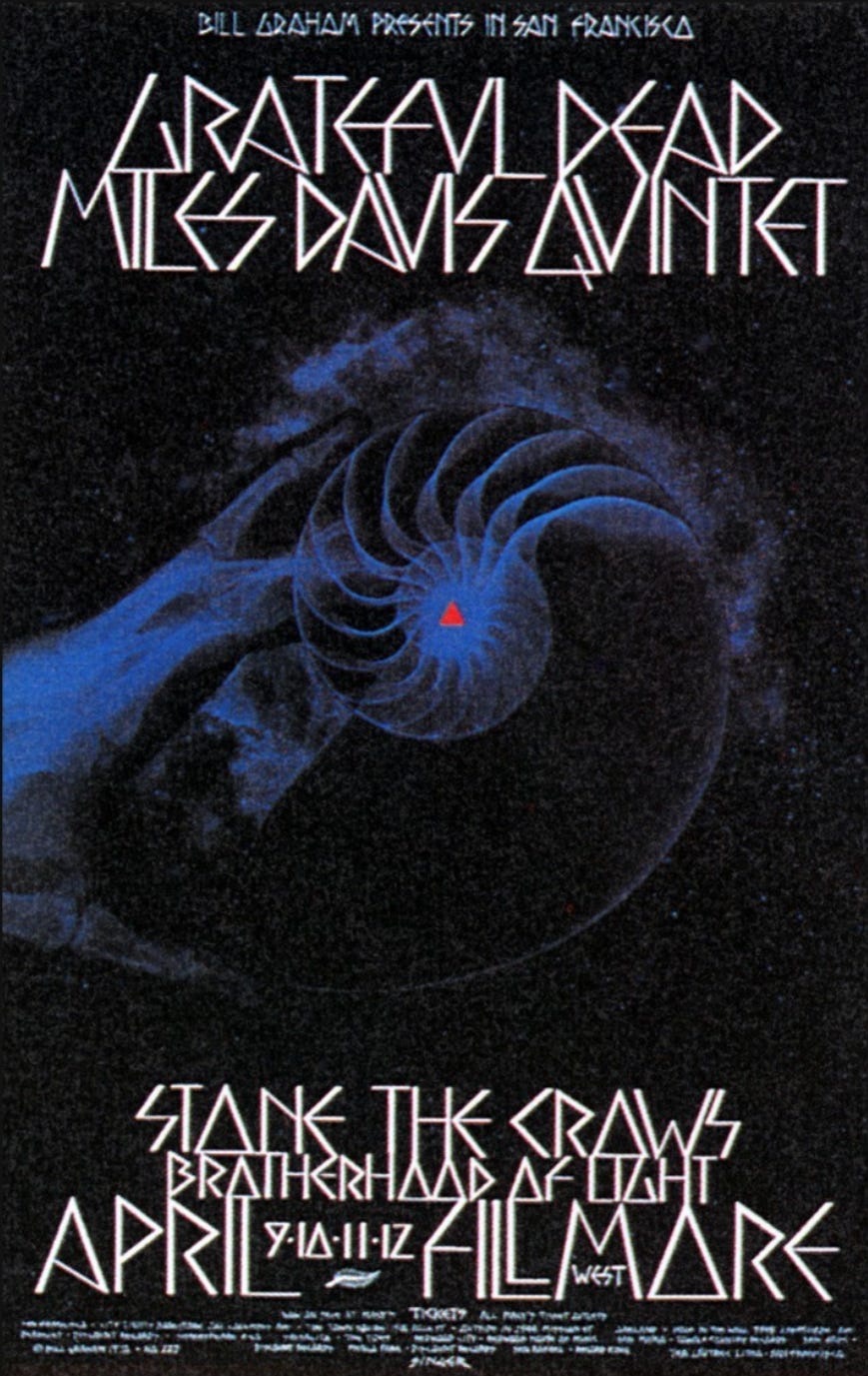

You’ll hear echoes of Herbie Hancock’s electric work and even some nods to Stan Getz’s Captain Marvel or early Return to Forever. But the most prevalent influence is electric Miles Davis. The Dead must’ve been taking notes when they played with Miles’s band at the Fillmore West in 1970. For comparison in terms of sound and vibes, here’s “It’s About That Time” from that April gig where Miles and the Grateful Dead shared a bill. The entire performance is worth hearing, but if you scrub about five minutes in and then go back to PITB, you’ll (hopefully) hear what I mean:

If that 74 “Playing in the Band” nods to Miles, here’s one from a year and a half earlier, on November 18, 1972, in Hofheinz, PA, that channels the exploratory power of mid-60s Coltrane. It’s also an exploratory version but more in-your-face and INTENSE. The mix also puts Phil Lesh’s bass work front and center, so those who want to hear what he brings will have lots to enjoy.

Since I mentioned that 1973 is probably the Dead’s most jazz-sounding year, let’s add one more PITB that goes into MANY different places and spaces. As the band closed out one of their finest fall tours ever, They spent a couple of days in Boston, where they unleashed this gem, which is split into two parts (for royalty payout reasons—back in the tape trading days, it was just labeled as one track):

Some Folks Look For Answers, Others Look For Fights

Historically, whenever I’ve gotten into a discussion with jazz enthusiasts about the Grateful Dead, we quickly get to a point in the conversation where facts about chords, scales, swing, structure, and other technical aspects of the improvisational “form” are laid out as arguments why the Dead AREN’T playing jazz. Some, many, or all of those arguments may be cogent. I’m not a musician and have no background in music theory. But again, I do not view this through a lens of formal music structure, musicianship, or technique. Not that I’m dismissing those things, as I’ve also heard Deadheads reduce their side of the argument to “the Dead never worried about chops,” which is 1) not true and 2) a lousy argument—listen again to any of those “Playing in the Band” examples and there’s plenty of musicianship afoot.

Before I matriculated to the worlds of either jazz or the Grateful Dead, I was a prog rock and fusion guy, so I rarely bought into the “technique doesn’t matter” argument, no matter what band was under discussion. Musicianship isn’t everything, but dismissing it entirely is ludicrous. Furthermore, wearing your admitted inability to play your instrument like it’s a red badge of courage is a load of shit. I’m sure there’s an audience for it, but I’m not on that mailing list. Claims that the Dead don’t have enough chops for jazz is a dead giveaway (boo!) that the claimant hasn’t meaningfully listened to their music.

Expanding on that notion, jazz chops are an obvious plus in the jam band/improv rock world. Phish was the heir apparent to the Dead. When their leader/guitarist Trey Anastasio sought a new bassist for his solo band, he didn’t pick from the many talented/established veteran bassists in Jamband-land. Instead, he chose the extraordinary Dezron Douglas, a member of Ravi Coltrane’s quartet and graduate of the Hartt School, where he studied under Jackie McLean. Blue Note guitarist Julian Lage recently sat in with rising jam band superstars Goose. Haven’t you heard of Goose? They’re the latest in a long line of heir(s) apparent to Phish, and while Goose’s choice of band name doesn’t strike me as a winner, they’ll likely be big enough to play Madison Square Garden within a year. Blue Note Records’ wunder-guitarist Julian Lage performed with them last month in Chicago, and they made a joyful noise. I’ve embedded this YouTube video to begin right at the guitar improv part. You’re welcome.

Jam band/jazz crossover isn’t new in the post-Dead era. Jazz guitar legend John Scofield, who teamed up with jam trio Medeski, Martin, & Wood in the late 90s, was a massive proponent of crossing those streams. It opened the eyes of many in the jam band world to a guitarist they weren’t previously familiar with, creating a lane for Scofield to tour and sell albums to an entirely new audience. Jazz musicians take note. Jazz fans, have a look/listen to this and see how well it works:

Believe It If You Need It, Or Leave It If You Dare

I’ve never met Phil Lesh, so while mourning a person with whom I’ve had no direct connection or personal relationship seems strange, the online outpouring of shared love, grief, and experiences has put me in a reflective state of mind. Looking back, my early indifference to the Grateful Dead’s music was superseded by a curiosity about the culture and lifestyle surrounding them. Curiosity became a fascination, which morphed into an obsession. Over time, the music revealed itself. Long story short, the Grateful Dead were (and remain) an enormous presence in my life. The friends, experiences, and music I heard along the way are all important in my jazz journey. I feel fortunate to have seen the Dead dozens of times in the 80s and early 90s, and my wife and I saw several terrific Phil Lesh & Friends shows at the Beacon when we were Manhattan dwellers. The Dead were in heavy rotation when our girls were born, and this poster has been on the wall for as long as they can remember. It has sunk in—Grateful Dead music is in regular rotation across playlists on all our devices and homes.

From a professional perspective, I’ve also taken pages out of the Dead marketing playbook and used the Dead several times in presentations at music marketing conferences. The Grateful Dead prototyped elements of the first social network. They led the charge in community creation and direct communication with their fanbase and were among the earliest adopters of the Internet. Their forward-thinking approach to allowing (and encouraging, by creating a dedicated Tapers Section) the free circulation of live recordings was an early analog template for peer-to-peer (P2P) music distribution a la Napster. The power of Napster was already apparent to me in April 1999, but it was underscored when I used it to acquire recordings of the 4/15/99 Phil Lesh & Phriends show just days after it occurred. Nowadays, the “instant live” and Nugs.net models allow professionally recorded live gigs to be in your hands within minutes after a gig ends. But back in 1999, when an eagerly awaited recording was often weeks or months from hitting your mailbox as you worked through setting up a trade or tape tree, digital files via Napster seemed like magic.

Community, marketing, and technology are three essential supports in the Grateful Dead story. Those things can be dissected, explained, and understood by most people. It’s the exploratory music of the Dead that some think sounds like somebody lost their car keys in the theater, and everybody solos simultaneously while trying to find them. Others insist on unpacking it to such an analytical extent that it sucks all the fun out of the room. I was that guy for a while. Don’t be that guy.

Of course, that leaves a couple of questions. Where should jazz fans looking to go deeper with the Dead go? And where should Grateful Dead fans seeking to expand their jazz horizons begin? I’ll tackle those in a forthcoming post and encourage those with opinions to sound off in the comments. I usually keep comments closed to paid subscribers, but I’m opening them up to all for this post as I’m curious. Play nice, please.

I'm 51. I've loved music for almost all of my life. I make music, I've studied it and delved into some of its fascinating realms. But I've never gotten into the GD. Recently I've been meaning to take the plunge. Your article has pushed me closer to it. Thanks and cheers.

A wonderful post Syd. Thank you! I'm 71 and in my late teens and not really that aware about different genres of music I got into the Dead at pretty much the same time as electric Miles and Coltrane. For some reason I was drawn to music with a high degree of improvisation and sonic experimentation and therefore it all made sense to me. The first times I got to see Miles were in 1969 (BBC recording at Ronnie Scotts) and 1970 (at Isle of Wight) the Dead in 1972 (Lyceum) and 1974 (Alexandra Palace). You're absolutely spot on about the Herbie/Miles/Capt Marvel/RTF influence on this period. I think Keith Godchaux was another conduit for this. (You picked out two of my favourite Dicks Pick's btw). Both the Dead and Miles were very important in bringing together different musical universes - Ornette Coleman, Stockhausen, Chuck Berry, The Carter Family, Sly Stone, Charles Ives etc etc. It seems very much the world now occupied by musicians like Bill Frisell, Julian Lage, Ambrose Akinmusire, Sam Amidon, Nels Cline and Esperanza Spalding.

Seeing that Fillmore West poster reminded me of Phil's memories of the gig from his biography:

".....we played a four-night stand at the Fillmore West, when we were faced with the unenviable task of following the great Miles Davis and his most recent band, a hot young aggregation that had just recorded the seminal classic Bitches Brew. As I listened, leaning over the amps with my jaw hanging agape, trying to comprehend the forces that Miles was unleashing onstage, I was thinking, What's the use? How can we possibly play after this? We should just go home and try to digest this unbelievable shit. ......... In some ways it was similar to what we were trying to do in our free jamming, but ever so much more dense with ideas — and seemingly controlled with an iron fist, even at its most alarmingly intense moments. Of us all, only Jerry had the nerve to go back and meet Miles, with whom he struck up a warm conversation. Miles was surprised and delighted to know that we knew and loved his music; apparently other rockers he'd shared a stage with didn't know or care."