May Mailbag: Swift Moves, Serge Pricing, and Soul Songs

Artists, Archives, and Owning the Narrative

I’m pleased to see that word is spreading about this gem of a record:

The duo of Hermon Mehari (trumpet) and Tony Tixler (Fender Rhodes) recorded Soul Song direct to 1/2” tape during a single November evening without a net. There are no overdubs, edits, Pro Tools fixes, splices, or digital trickery—just 33 minutes of pure, analog, unfiltered musical synergy with jaw-dropping sound.

Each side has two decidedly non-standard cover tunes, an original and an improvisation. The reworkings all work! Stanley Cowell’s “Maimoun” and George Duke’s “The Black Messiah” are delightful. It took me a moment to place Bobby Hutcherson’s “Hello to the Wind,” which was also superb. I wasn’t familiar with “Laini,” by Martinican pianist Marius Cultier, but I dig this track, which closes the album with a playful, upbeat vibe. Original compositions, such as “This Is Our Fantasy” and “Poem for the Oppressed,” add personal narratives to the mix. At the same time, the improvisations reveal a partnership that is equally capable of spontaneous composition, arranging, and interpretation.

I was concerned that this would be too sparse or minimalist to hold my interest. I was wrong, and Soul Song hasn’t left the “heavy rotation” pile adjacent to my turntable in a month. Vinyl is limited to 500 copies worldwide. Digital editions are unlimited.

Serge Chaloff: Bari Tone Poet

If Mehari and Tixier are conjuring something fresh from scratch, Serge Chaloff’s Blue Serge reminds us that spontaneity is timeless. Different tools, different era, same spirit of uncompromising artistry.

Serge Chaloff’s Blue Serge arrived in stores this past Friday, a welcome reissue of a record that (hopefully) will reach the wider audience it always deserved. It’s the latest title in the Tone Poet series, and the Blue Note team has given this quartet session their usual top-shelf treatment with a new cut directly from the master tapes and a high-quality vinyl pressing housed in a Stoughton jacket.

It was an honor to write the liner notes included with this new edition, as this is my favorite baritone sax recording of all time, and I’ve excerpted the opening paragraph below. Serge Chaloff may not be a household name, but his story makes this record all the more remarkable. Drop the needle on this record and you’ll be astounded at what you hear. Even vinyl skeptics have difficulty believing that this is a mono recording from early 1956. It’s a perfect jazz record for any occasion.

Jazz is synonymous with reinvention and resilience—two truths vividly embodied in the story of Serge Chaloff. His career was a study in contrasts: a bebop virtuoso renowned for striking agility and lyricism on the baritone saxophone, yet a man whose outrageous behavior and substance abuse nearly eclipsed his artistry. ‘Blue Serge,’ recorded just a year before his untimely death at age 33, remains Chaloff’s definitive statement. Most baritone players embrace their instrument’s rough edges and natural gruffness, but Chaloff reimagined its possibilities. He’s seductive and whisper-like during soft passages, only to unleash a baritone blast during the next bar that would stop a freight train in its tracks. That was Serge Chaloff’s superpower: instinct and technique fused to leverage dynamics into compelling storytelling. He delivers every note, phrase, and line with a perfect balance of intent, urgency, and restraint, using his musicianship to converse, not impress. Like other artists who found solace in their instruments, ‘Blue Serge’ carries the unmistakable tone of a man celebrating a new lease on life. That said, listening in hindsight, ‘Blue Serge’ feels eerily prophetic, like reading the final pages of a novel while knowing the protagonist won’t survive. Though hints of fragile awareness permeate his performance, Chaloff had no idea during the recording sessions how little time he had left.

—excerpted from Blue Serge liner notes © 2025 Syd Schwartz/Jazz & Coffee

Track of the Week: “As Fate Would Have It”

Can’t. Stop. Listening!

Kevin Brunkhorst is an Associate Professor of Music at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia. He chaired the music department there for several years, and is an alumnus of UNT (and was a member of their notorious One O’Clock Lab Band), with four albums of original work under his belt as a leader. This is from his forthcoming album, After the Fire, which is set to arrive in July. More here. Echoes of Ralph Towner, Bill Frissell, Pat Metheny, and epic jazzscapes of ECM abound, but those reverberations are more homage than “me too.” If you dig what Charles Lloyd has been doing these last few years, you’ll LOVE this.

May Mailbag: The Taylor Swift Business Era

As usual, a lot is happening in the music biz right now. But my inbox is still overflowing with questions, hot takes, and medium-spicy Swift opinions. Hell, this story had new facets as recently as lunchtime today! So let’s break it down.

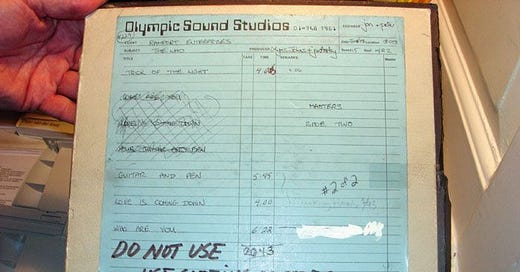

What actually happened with Taylor and her master tapes? (simple version)

At 15, Taylor Swift signed to Big Machine Records. Like most new artists with big dreams and zero leverage, she traded ownership of her master recordings for promotion, radio play, and a shot at not spending her adult life covering Jewel songs at state fairs. That’s how the system works: labels take the risk, artists give up the rights.

But then Taylor didn’t just become a star—she became a billion-dollar empire. So when Big Machine sold her masters to Scooter Braun (Kanye West’s manager, not exactly Taylor’s bestie), and did so without her knowledge or consent, it ignited an emotional, ethical, and financial custody battle over one of music’s most valuable catalogs.

Enter Scooter: Braun’s “Shocked Pikachu” Moment

In a recent interview on the Diary of a CEO podcast, Scooter Braun said he was “shocked” by Taylor’s reaction. He claimed he thought acquiring Big Machine would be an “exciting” opportunity to work with her and other artists, despite knowing she had long-standing issues with his clients Kanye West and Justin Bieber.

His actual words:

“I had a feeling she probably didn’t like me… but I thought that once this announcement happened, she would talk to me, see who I am, and we would work together.”

Spoiler alert: she didn’t. Instead, she hit post on Tumblr, called the move “manipulative bullying,” and launched one of the most successful artist-driven campaigns for music ownership in modern history. Braun now says he “can’t worry about everyone’s niece being mad” at him. So, yeah. He’s moved on. But Taylor hasn’t forgotten.

So what did Taylor do next?

Taylor clapped back with a savage flex: she re-recorded all those albums, not as a petulant teen flipping the bird, but as a savvy industry player using a strategic power move, successfully devaluing the originals by flooding the market with Swift-approved alternatives. It’s like rewriting the rules so that the Director’s Cut becomes canon, and the original theatrical version is a pale imitation.

Then came the twist: she bought the originals back (Braun had flipped them to Shamrock Capital). Not because she had to. Because she could. And because it was right.

Wait—so she signed a bad deal, redid all her work, and then paid a fortune for something she’d made worthless? Sounds…extra.

You could call it “extra.” Or you could call it extraordinary.

If Big Machine’s contract didn’t block re-recordings or include a non-compete, then the “bad deal” label might apply more to them than to her. Their real mistake? Underestimating Taylor Swift—legally, artistically, and strategically.

And those original masters aren’t worthless. Swift’s re-record strategy turned Shamrock’s asset into a slow-burning liability. She bought it back at a discount, sure—but in Swiftworld, cultural capital is currency. Empowerment, authorship, and control aren’t just nice-to-haves. They are the brand.

So she torched the village, salted the earth… then bought it and opened a boutique hotel?

Exactly. With themed rooms, limited-edition keycards, and a “Mean Lefsetz Green” vinyl edition available exclusively in the Short Skirts ‘n T-shirts hotel gift shop.

Cool. So, should every artist demand re-record options and master ownership now?

Let’s not get carried away. Taylor has leverage that most artists don’t. If your band has 5K streams and a group Venmo for post-gig burritos, you’re not walking into a label meeting demanding master ownership. Labels still hold the cards, and yes, they’ve updated the fine print. “Swift clauses” are now baked into new contracts to address precisely this scenario.

But Taylor’s actions did change the conversation. Artists are asking smarter and tougher questions. Managers are prioritizing ownership from day one. And fans are starting to follow the money.

The game has changed—even if most observers are still studying the instant replay.

Taylor’s not just changing the rules—she’s playing an entirely new game. But what of the veterans who are ready to walk off the field entirely?

Different career stage, different goals.

Those artists are planning exits. Stevie Nicks, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen—they took big checks in exchange for handing off their catalogs, usually to private equity firms or rights aggregators betting on syncs, licensing, and the long-tail of nostalgia.

There are good reasons for this, including estate planning, liquidity, and maintaining family peace. Especially in states like New York—where the estate tax cliff is brutal—selling now and paying 20% capital gains might beat leaving heirs to pay 37% on royalties plus estate taxes. Especially if those heirs can’t tell a sync license from a Spotify stream.

But there’s a tradeoff: you cash out, but lose control. Forever.

I loved working with KT Tunstall back at Virgin, and I’d be happy for her if she were to sell her catalog for enough money to set her up for the rest of her life. But the idea of a Depends ad featuring “Suddenly I Pee”? And before anyone thinks that’s taking things too far, go ask Steppenwolf how they feel about “Born to Be Wild” being synonymous with Pampers diapers these days.

Taylor’s move is different.

She’s not exiting. She’s expanding. Taylor turned her catalog into a closed-loop system where every stream, sync, and sale flows back into her house. Her business strategy was never about revenge. It was a multi-year, multi-platform ownership campaign.

Taylor didn’t just beat the system. She built her own.

That’s the simple version?

Nothing in this business is simple. However, if you're looking for a solid, Swiftie-neutral timeline, consider coverage from the BBC and The Guardian. For daily dispatches with a little less snark and a lot more nuance, I recommend Unlimited Supply, the excellent music industry podcast hosted by Lars Murray.

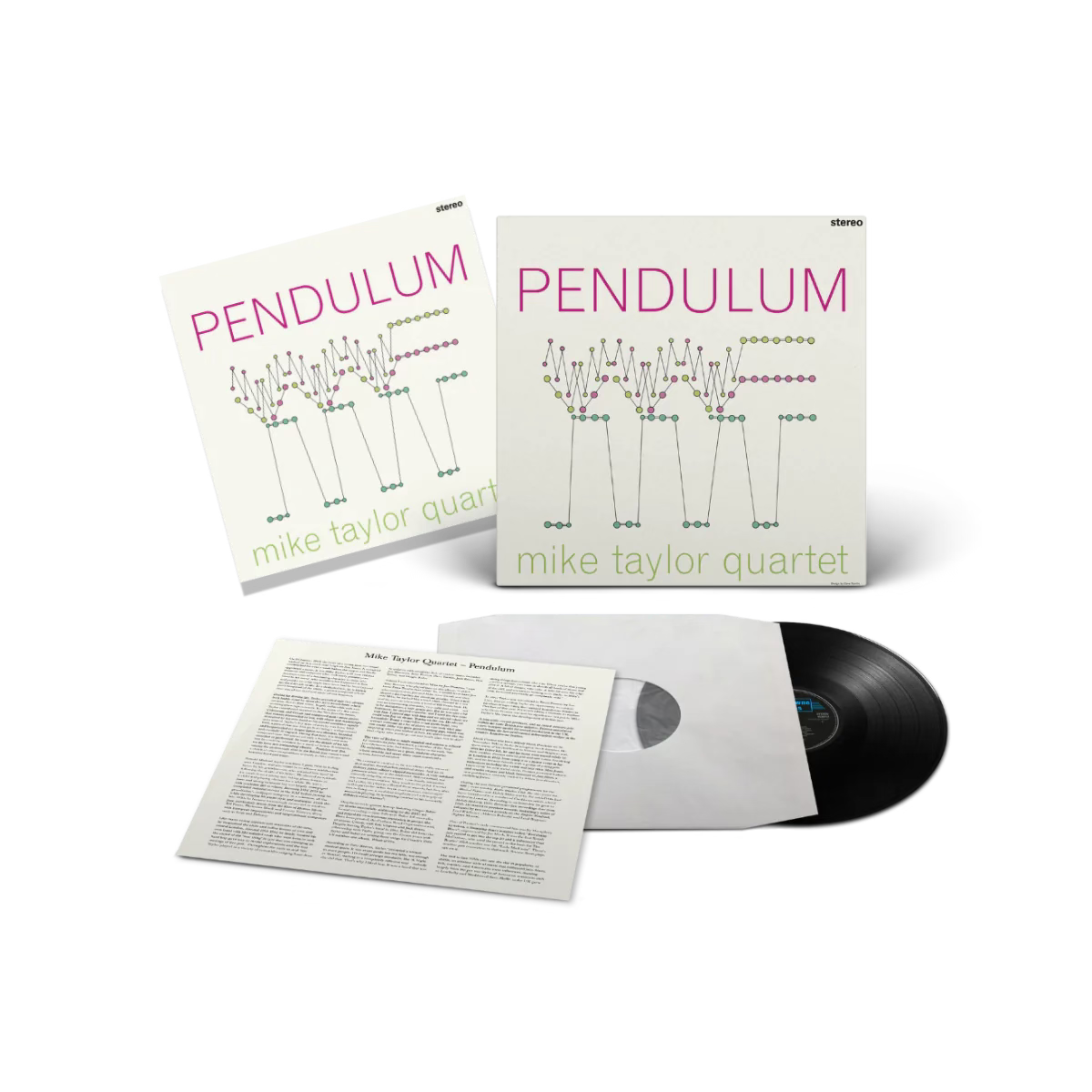

A Different Taylor: An Obscure Jazz Record Ready to Claim Its Destiny

Speaking of Taylors—here’s one more, with far fewer TikTok montages and a whole lot more modal freedom. Mike Taylor may not have Grammy awards or a billion-dollar empire, but his Pendulum is swinging back into the conversation.

When I invoke this record during exchanges about “best jazz records of all time that nobody seems to know about,” it’s the one that piques the most curiosity. The Everything Jazz website says Taylor’s “story reads like that of a grand opera, embracing exceptional music, high drama, mental illness, drugs and an untimely early death.” The key phrase is “exceptional music.” If for some reason you’re one of the few who noticed Taylor’s name credited as a composer on your Cream Wheels of Fire album for "Passing the Time", "Pressed Rat and Warthog" and "Those Were the Days" (music: Mike Taylor, lyrics: Ginger Baker), don’t expect the inside/outside jazz of Pendulum to sound anything like that. It sounds like this:

I’ll have a lot more to say when my pre-order arrives at my doorstep in July. And I can’t wait to read the liner notes by Tony Higgins, who’s one of my favorite writers.

The Mike Taylor Quartet's Pendulum is brilliant. Grab a copy before everyone else does.

Finally: Fakery—It’s Not Just For Breakfast Anymore.

From a long-lost jazz record finally getting its flowers to music that never really existed in the first place—welcome to the weird, wide-open world of fakery, frauds, and algorithmic allsorts. Longtime readers may remember a story I posted last September about fake artists pissing in the streaming pool:

Wired Magazine recently published a thorough investigative piece on the latest developments, which is extremely good reading. Inspirational quote:

TECHNICALLY, IT’S NOT illegal to make a bonkers amount of AI-generated music and put it on a streaming service. Tacky, yes. Disrespectful to the art form, probably. But not necessarily against the law. —Wired, May 2025

Until next time!

Hey Syd, nice write. Intrigued by the Mike Taylor album, but I'm noticing not one, but two re-releases coming out the same day, the other one being "Trio." Do you know that one, any thoughts? Thanks