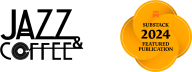

No Room for Squares—great title, great album cover, great music—all that’s been missing is a quality vinyl pressing that won’t break the bank. Now, we can rejoice that our wishes have been granted. Blue Note Classics continues its run of excellence with an all-analog reissue, cut by Kevin Gray, that’s available now. I’m pleased to say that having A/B’d it against my 2XLP 45 RPM Analogue Productions and my Heavenly Sweetness pressing, it’s the winning edition. The new cut sports deeper, tighter bass (especially on “Up A Step”), crisper drums, and better separation between instruments in the overall soundstage—you get a realistic sense of where everyone in the studio is. Drop the needle on No Room For Squares, which banishes the rest of the world to the background, just like a good record should!

A compelling aspect of Hank Mobley’s music is that his compositions and records are accessible, even if you’re relatively new to jazz. That doesn’t mean they’re boring or unsophisticated, but Mobley never developed a reputation as a technical groundbreaker like Coltrane, a compositional wunderkind like Shorter, or a stylistic innovator like Rollins. But to better understand Mobley’s magic, putting his music in context is a requirement.

No Room For Squares heralds the start of Mobley’s third and final burst of artistry based on the three broad phases I use to subdivide his career:

Triassic Mobley begins with his first recordings under Max Roach’s leadership in 1953, through the formation of the Jazz Messengers and the nine albums he recorded as a leader for Blue Note, Prestige, Savoy, and Roulette through 1958. Around then, Mobley began dabbling in narcotics—a habit that would drag him down more than once throughout his career—leading to his first arrest and jail time.

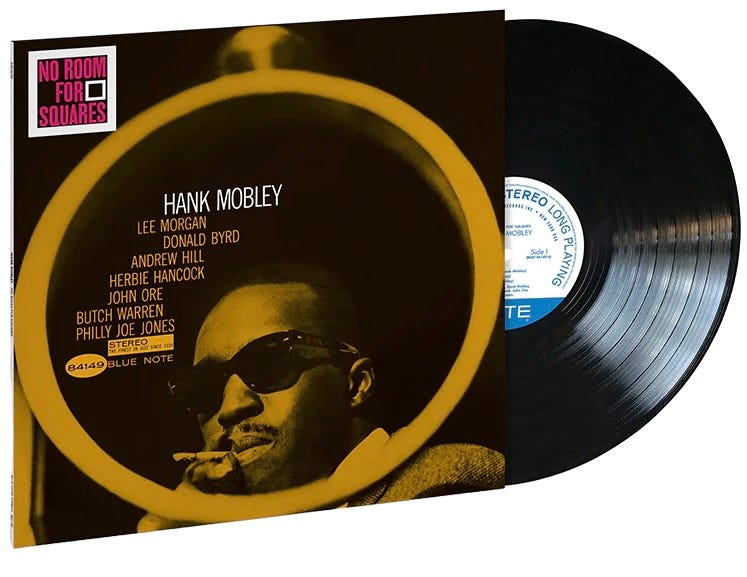

One of the many fine hard-bop albums from the first era of Hank Mobley’s career, Mobley’s Message was recorded in ‘56, and released on Prestige in ‘57 The Jurassic Mobley era opens as Mobley returns from a year behind bars in 1959, reconnecting with his old pal Art Blakey and donning his Jazz Messengers name badge once again to get his chops back in shape. Once he’d regained his sea legs, Mobley began what many consider his Main Sequence: four albums that remain among his best work. Roll Call, Workout, Another Workout, and the iconic Soul Station are hard-bop classics. Soul Station is one of the first jazz CDs I ever bought and remains on my short list of recommendations for those looking to build a jazz library—it’s accessible but not lightweight. In addition to leading this impressive run of albums for Blue Note, Mobley was invited to join Miles Davis and lend his tenor skills to Someday My Prince Will Come, and live sets At the Black Hawk and At Carnegie Hall. However, Mobley’s stint with Miles Davis was far from a dream gig. Mobley—a saxophonist whose name would become synonymous with the word “middleweight”—was caught in the middle with Miles. He was guilty of two crimes—not being John Coltrane or Sonny Stitt (whom he replaced) and not being Wayne Shorter (whom Miles wanted for the gig but couldn’t get—yet). As a result, Miles turned his frustrations directly to Mobley, at first hazing him like any new band member but growing progressively more mean-spirited. Mobley’s skin could’ve been thicker than the layer of fat on a high school cafeteria meatloaf, but it was no match for Miles’s relentless taunting. While Mobley may have been leading the most robust sessions of his career, he became despondent and weary of others’ expectations, returning to the needle and spoon. Jurrasic Mobley may have been a short epoch but a busy one that yielded renowned music, but a troubling end—addiction and prison beckoned once again.

As Hank Mobley was largely absent during 1962 due to substance abuse or trouble with the law, Cretaceous Mobley began in 1963. And while its beginnings were modest, they were mighty. For starters, while it’s difficult to find any silver lining in the Miles era—fraught with a frustrated/frustrating boss, low self-esteem, and the re-emergence of Mobley’s substance abuse demons—Mobley evolved under pressure. His writing began to embrace the modalities Miles pioneered with Kind of Blue, and his “middleweight” style became rougher around the edges, incorporating tension/release building blocks, emotional bursts of notes that emphasized registers at the high and low ends of the horn, and less predictably behind the beat. Miles may have been pining for the fjords when it came to Coltrane’s absence, but Mobley chose instead to take a page or two from Trane’s playbook where it would help without stealing his licks or blatantly copying his style. This facet that adds special sauce to Mobley’s final run of albums, which—from my perspective—is an under-appreciated quality that deserves reassessment.

Mobley led only two sessions in 1963, and the resulting music was—three decades before the term was coined, then used rather differently—chopped and screwed. Scattered across several albums, Mobley’s final epoch was marked by a flurry of increasingly interesting compositions and musically deep sessions that Blue Note would produce, vault, and then issue partially and/or posthumously. Some were released as intended, some tracks were tacked onto CD reissues as bonus tracks, or compiled as entirely new albums as they had no home elsewhere. Mobley’s frustration with Blue Note’s approach increased until the notoriously press-shy Mobley erupted in anger during a rare interview, expressing a ginormous WTF as to why Blue Note kept asking him to record when they seemed to have little intention of ever releasing the half-dozen records he’d already given them!

Vaulted sessions and the decision-making around them is a subject

for a whole other post, but suffice it to say Mobley wasn’t alone—Blue Note put plenty of mid-60s sessions on ice from artists across their roster, from the less-commercially inclined stylings of pianist Andrew Hill to proven hitmakers like Lee Morgan. That was little solace to Mobley, who remained bitter about this stranglehold over his music until the end.

Mobley’s output was modest in ‘63, so while it’s messy, acquiring and organizing it is a manageable lift. The table shows the tracks on this new vinyl edition of No Room For Squares

If you can find it reasonably priced, my favorite way to enjoy the March 7 session is through the Music Matters release, The Feelin’s Good. Music Matters, who are currently dormant as far as I know regarding new products, produced a stellar run of audiophile Blue Note reissues that will stand the test of time. The Feelin’s Good is their team crafting a release in the spirit of a classic BN record. It is long out of print, and as great as it sounds, the second-hand prices are ridiculous. If you want to hear this March 7 session as sequenced, here’s a lossless (and Hi-Res) digital edition as a Qobuz playlist: