Grammy Theft Auto: Herbie Hancock Steals the Show

New Standards, Old Man Shouts at Shrink Wrap, and Reviews That Can't Lose!

My annual Grammy viewing experience used to be a dynamic mix of genuine interest, opportunistic snark, professional responsibility, morbid curiosity, and mild indifference. Once I dispensed with the word “awards” and primarily viewed the event through a lens of entertainment, the Grammys were more fun to watch. I especially enjoyed the performances from the Best New Artist category nominees this year.

Not every performer or genre may be your cuppa. Still, it’s difficult NOT to be impressed by Doecii, Chappell Roan, RAYE, Teddy Swims, and the other Best New Artist nominees. There’s a lot of talent in that room. However you feel about the music industry, the Recording Academy, awards shows, and their associated politics/drama, it’s reassuring to see creativity shining brightly and the entertainment community coming together for Los Angeles after the wildfire disaster. Skeptics may want to look closer at this new generation of talent. I saw a ridiculous post-Grammy argument online about rap, television performances, and lip-syncing that smacked more of racism and a fear of getting old than genuine music criticism—don’t be that person, please. Doecii certainly was not lip-syncing at her Tiny Desk concert earlier this year, which was GREAT:

It wasn’t the youngsters performing that got my beanie twirling, though. Jazz rarely gets a big spotlight moment during the primetime broadcast, so seeing Herbie Hancock in action during the Quincy Jones tribute was a huge thrill. It’s magic watching the years fall away as his hands touch the keys, and it is amusing to see made-for-television backing bands—even the great ones—sweating to keep up with him. Herbie is an inspiration, and I hope I’m in the physical and mental shape that Herbie is in when I’m 84. Herbie was inspiring enough to push aside the drama, nonsense, and debates over all the other Grammy punditry that passes for analysis (except maybe for Chappell Roan’s brave speech) and go on a Herbie Hancock bender instead.

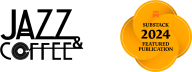

My trip down the Herbie Hancock rabbit hole peaked with a long dive into The New Standard. I was primed to do so, having been grooving hard to Michael Brecker’s Tales From the Hudson lately. That record hails from the same era as The New Standard and similarly features the bass/drum duo of Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette. I’ve also been in deep communion with Steely Dan’s Katy Lied of late, and The New Standard contains a cover of “Your Gold Teeth II.” I’m obsessed with that song for many reasons, but primarily because it includes THE BEST guitar solo ever recorded. That’s a hill I will die on

I remember when The New Standard was first released in early 1996. By then, Herbie Hancock had already reimagined himself multiple times, ranging from the beautiful, inspired free-bop of Maiden Voyage to the intergalactic funk-fusion of Head Hunters and the electro-futurism of Future Shock. Though I was a big fan, I was also picky and hadn’t connected with most of his electric-leaning records of the 1990s. Herbie’s return to acoustic piano was cause for celebration, but an album of jazz reinterpretations of pop songs was cause for skepticism.

I shouldn’t have worried—The New Standard wasn’t some cynical attempt to make jazz “relevant.” Herbie hypothesized that well-crafted popular songs could serve as worthy vehicles for improvisation, just as Broadway standards had for decades before. The fact that it didn’t play like a gimmick is a testament to the musicianship of Hancock and his hand-picked band of sonic assassins: Michael Brecker on tenor and soprano sax, John Scofield on guitar, Dave Holland on bass, Jack DeJohnette on drums, and Don Alias on percussion. Herbie Hancock had far too many accomplishments in his rearview mirror for anyone to believe this was a crossover cash grab or pandering to commercial interests. This was Herbie bringing the past forward into an all-star modern jazz summit.

Hancock and his ensemble didn’t just play the hits; they deconstructed and rebuilt them from the ground up. The opening track, “New York Minute," is the most successful reinvention. Doubling the original in length on The New Standard and then doubling again in this live version below, “New York Minute,” is the litmus test for whether this record is for you.

Nirvana’s “All Apologies” is transformed into a reflective, almost chamber-like meditation, with Brecker’s soprano sax floating delicately over Hancock’s chordal shifts. Steely Dan’s “Your Gold Teeth II”—a song already dripping with harmonic intrigue—becomes a laboratory for Scofield’s angular, unpredictable guitar work. It sounds like he’s falling out of a tall, demented blues tree and hitting every bop branch on the way down. That said, it’s one of the few tracks on The New Standard that puts the core melody of the song front and center, making it easier to follow for those listeners who are still coming to grips with the ways of jazz.

A personal highlight is Prince’s “Thieves in the Temple,” which, in its live performances, would stretch past the 20-minute mark as Hancock’s band turned it inside out. Even the studio version is a surprising journey, as the expected melodic hooks are implied more than stated, becoming signposts that guide the musicians through different rhythmic and harmonic territories.

Some tracks stay close to their mothership, which is probably the most frequent criticism I hear about The New Standard. The Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood” retains its familiar, folky introspection and deepens in complexity but loses its most prominent hooks. I’m not sure the outcome is worth the tradeoff on the studio version, though Hancock’s lethal band did a lot more with it onstage. Still, Dave Holland’s rock-solid yet elastic bass foundation is a marvel. It doesn’t best Paul McCartney’s pop precision but presents a wonderfully malleable alternative. Meanwhile, Peter Gabriel’s “Mercy Street” is drummer Jack DeJohnette’s moment to shine, as he crafts an intricate, hypnotic groove that invokes a dreamy atmosphere, giving plenty of breathing and stretching room for everyone to play within the new arrangement.

The guy who dazzles throughout is Michael Brecker. By 1996, he was well-established as one of the key post-Coltrane stylists and the hero of The New Standard. His solos throughout the record are excellent. The record delivers, but let’s be honest—Hancock’s New Standard All-Stars were at their best live. If you aren’t sold on the record, here’s the band just over a year after the album's release at the Warsaw Jazz Festival, taking three tunes out for a good time:

The New Standard never achieved the iconic status of Head Hunters or Maiden Voyage, but it holds a unique place in Hancock’s discography. It serves as a bridge, both stylistically and historically—introducing rock and pop fans to jazz while reminding jazz diehards that standards are what you make them (as long as you’ve got skills to back it up). The New Standard doesn’t chase trends—it absorbs them and processes them before reflecting them back through the lens of some of the finest improvisers of the era. In doing so, it supported Hancock’s hypothesis: a great song is a great song, no matter where it comes from.

I’ve always loved this record, yet I defend it to fellow enthusiasts more often than celebrate it. If you haven’t spun The New Standard lately, I urge you to revisit it. Because if jazz has taught us anything, it’s that what’s “new” is just a matter of perspective. All digital editions are worthy if you’re looking for format advice on adding this album to your library. However, if you can acquire the Japanese-only double CD release, it contains the bonus track of “Your Gold Teeth II,” and a second disc with about an hour of live material from 1996. My vinyl edition is the 2019 South Korean pressing, which sounds terrific. Two US vinyl pressings via Third Man from 2023, which I’ve not personally heard, have mixed feedback online regarding warps and pressing quality, so YMMV. About a dozen FM and satellite radio broadcasts of Herbie’s New Standard All-Stars band circulate in trading circles for those who can’t get enough, including a more extended edition of that Warsaw gig posted above.

Vinyl Inadequacy: Shrink Wrap Leads to a Shrink Rap

I still remember buying Pink Floyd’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason on release day and getting it home. My estimate of the total time between closing my bedroom door, removing the shrink wrap, packing a bong hit, dropping the needle, and achieving escape velocity? 46 seconds.

It wouldn’t matter which record I was describing. Even if you were being extra careful, this NEVER took more than a minute. It wasn’t a race, of course, and rushing the process might result in a paper cut (annoying), a bent cover corner (worse), or a spilled bong (tragic). Besides, if all else failed, there was always the denim friction trick, so long as you did it in the privacy of your bachelor pad. Imagine your wife finding you furiously sawing an LP back and forth on your denim-clad thigh, grunting, ‘Come on, you bitch!’ through gritted teeth. This guy gets it:

So, Dear Jazz Dispensary,

I don’t know if anyone from your team is reading, but the industrial-grade, Fort Knox-level plastic on the reissue of Patrice Rushen’s Prelusion was a little extra. My struggle to open that LP was hilarious—borderline “where’s the camera?” It gave me PTSD flashbacks to my first bra removal experience, which, for the record, was consensual but took the entirety of Cygnus X-1: Book II to figure out. The album brought me a lot of joy, but the cover is now VG- from flecks of cuticle, bloodstains, and wounded pride. There’s a brand new hole in my self-esteem cup. Thanks, Jazz Dispensary bullies. I'm sending you the bill if insurance doesn’t cover the therapy session.

Instagram Recaps Recapped

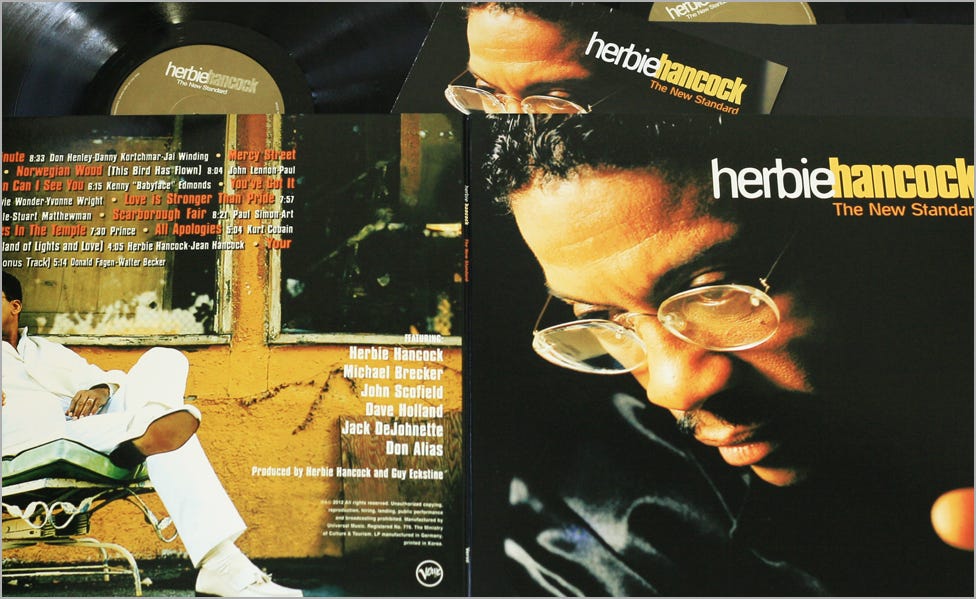

Art Blakey The Freedom Rider

Art Blakey’s The Freedom Rider—a testament to the symbiotic relationship between jazz and the civil rights movement—is a sonic rallying cry to kick off Black History Month 2025. Recorded in 1961 for Blue Note Records, this album is a swinging history lesson encapsulating an era fueled by the activism required to catalyze societal transformation. In 1961, a group of courageous people called the Freedom Riders risked life and limb, challenging segregation in the Deep South with their model of nonviolent resistance and strategic planning. Blakey’s percussive narrative pays homage to their resilience as he leads his world-class band to join him in a call to action that resonates more than six decades later. Lee Morgan-trumpet, Wayne Shorter-tenor sax, Bobby Timmons-piano, and Jymie Merritt-bass are all in lockstep under Blakey’s command. Blakey sounds more emotionally invested here than usual because he literally had skin in the game. Art Blakey was brutally beaten by police in a racially charged confrontation while on tour during the 1940s, requiring surgical intervention and the placement of a steel plate in his head. This record wasn’t just musical or political—it was personal. The Freedom Rider not only commemorates a pivotal historical movement but also underscores the enduring power of music as a vehicle for social change—a reflection on the past that can inspire the current socio-political quagmires. The movement isn’t over, and neither is the fight. But as long as there’s rhythm, there’s resistance. Drop the needle. Pour another coffee. Keep pointing out injustices as you see them. And if you see a good fight, get in it.

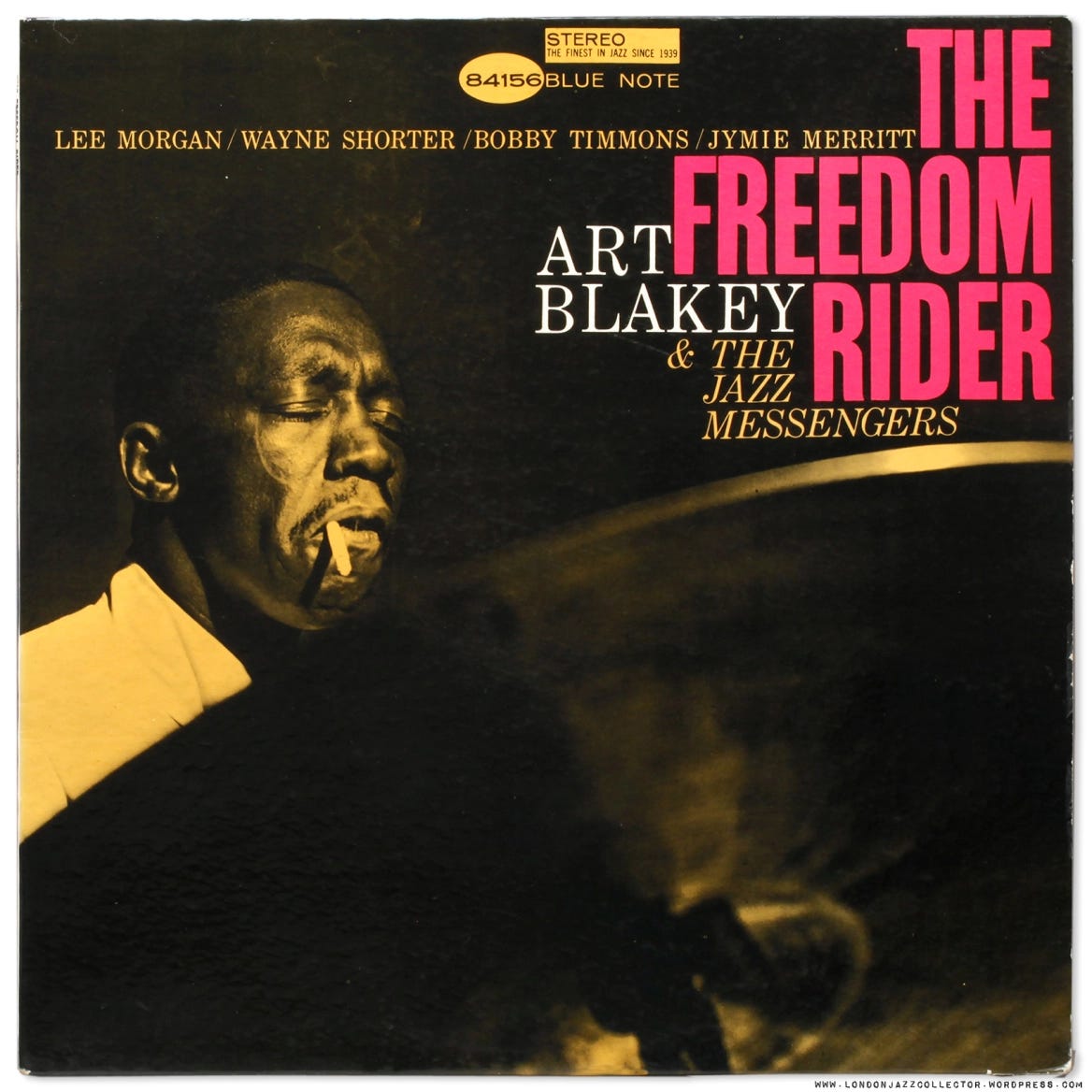

Brand X Livestock

A double celebration—Fusion Friday and 74 laps around the sun for drummer Phil Collins this week! I’m still salty about Collins’s “One More Night,” among my least favorite songs and (ironically) my prom theme—a fitting end to my high school experience. It encapsulated the omnipresence of Collins, who, from my perspective, had sold out his prog rock (Genesis) and jazz-fusion (Brand X) cred in favor of becoming MTV’s flavor of the week. Not that my proposal of The Resident’s “Smack Your Lips (Clap Your Teeth)” stood a chance—and explains why I was voted Most Likely to Drop The Bomb by the senior class—but “One More Night” is weaksauce. It’s undoubtedly milquetoast compared to Brand X, the intergalactic fusion outfit that Collins summoned from another dimension once he decided Genesis was too restrictive for his drumming chops. Collins was right. If you’re proud of nailing the famous “In the Air Tonight” fill on air drums, you’ll throw your back out attempting anything on Unorthodox Behavior. It’s like Britain’s answer to the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Refined intensity. Collins’s polyrhythmic precision is matched by surprising power, and it wouldn’t surprise me if his drum kit was a heap of smoldering rubble by the end of the session. Fretless bass from low-end hero Percy Jones blends the intricacies of Jaco Pastorius with the attack of George “The Animal” Steele. At the same time, guitarist John Godsall stalks his guitar fretboard like a velociraptor on Adderall. In short, if you want to kick back and relax, a Windham Hill record might be more your speed. But grab any of the first few Brand X albums if you’re in the mood for unleashed, undiluted, and occasionally unhinged musicianship atop solid compositions. GREAT sounding recordings, too. Cheap heat in most second-hand bins. My favorites are Unorthodox Behavior, Moroccan Roll, Masques, and Livestock live album. Fun facts courtesy of Greg DeBonne: Brand X guitarist John Godsall (RIP) is the guitar player on Toni Basil’s “Mickey” and Billy Idol’s “Rebel Yell.” Who says musicianship was dead in the 80s?

Prime, Grade-A Syd!