The Uncanny Allure of Japanese Jazz (J-Jazz)

The Art of War, War of Art, and Tekisei Ongaku—Enemy Music

I was scanning the morning music news feeds when a headline caught my eye:

How a Japanese medical student and local businessman made one of the most coveted records of all time.

My curiosity was piqued as the undertow of the subheadline continued to pull me in…

“Used as a business card by the man who funded the recording in his basement and after whom the album is named, Tohru Aizawa Quartet’s Tachibana is one of the rarest Japanese jazz records of all time. Featured on BBE’s new J-Jazz compilation, Tony Higgins tells the bizarre story behind this real-life holy grail.”

And by the time I got to this sentence:

This album has all the necessary components of such cultish impulse: mysterious and vague details about its origin, brief existence, superb craftsmanship and skill, and scarcity of the object…

I was all in.

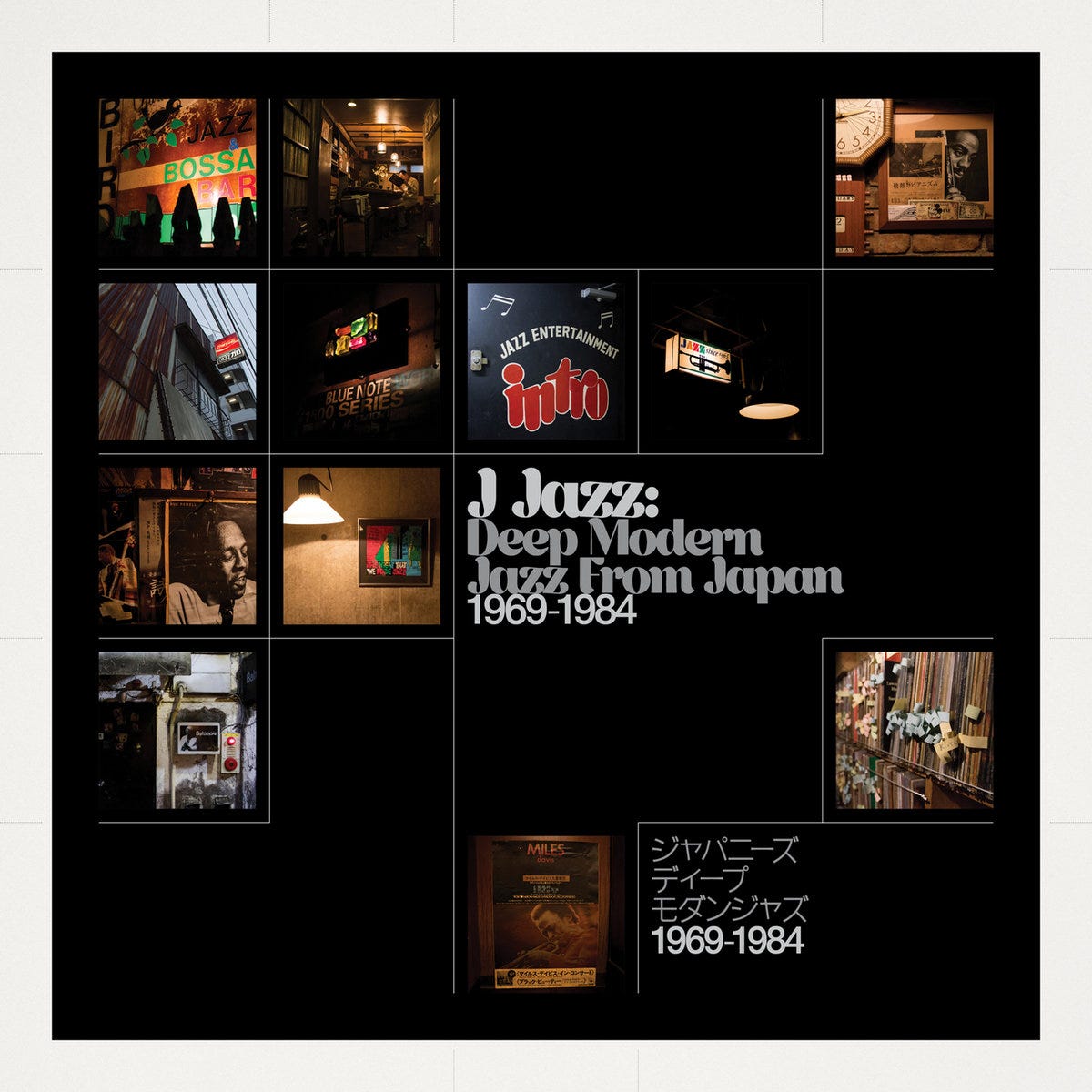

Nothing enhances music more than great storytelling, and Tony Higgins’s article about Tohru Aizawa Quartet’s ‘Tachibana’ was a story that motivated me to buy J-Jazz Volume 1: Deep Modern Jazz From Japan 1969-1984. (DMJFJ) That was back in 2018 when it topped the list of my favorite albums that year and has remained in steady rotation ever since—it’s an album with incredible replay value. I’ve also recommended it to more people than almost any other record in my library, and it has—to date—a 100% success rate.

Volume 1 was just the beginning. Tony and fellow subject matter expert Mike Peden opened my eyes and ears to an entire world of music I’d NO idea existed. Imagine being an ice cream enthusiast exploring all 31 flavors of Baskin & Robbins, only to look down a hallway you’d never noticed before and discover a room with ANOTHER 31 flavors.

Japanese Jazz: A Brief, Incomplete History…

The nascent jazz scene in Japan of the early 1920s had achieved mainstream popularity when it disappeared in December 1941. When the USA declared war the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese government outlawed jazz as tekiseiongaku—enemy music. But jazz roared back with a vengeance in postwar Japan, initially filling the void of absence and imitating American variants. A fascinating confluence of factors reimagined the art form as evolution gave way to innovation.

Postwar occupation by US troops drove the initial surge, as armed forces radio played the latest Stateside jazz releases and stationed military personnel imported jazz records into the country. Jazz was in the air during the mid-40s to early 50s. But the demand for live jazz brought local players into the fold, as Japanese musicians—most recently wielding rifles and bayonets rather than saxophones and drumsticks—were eager to catch up on what they’d missed. Work in the recovering economy was scarce, but entertaining the troops provided rare paying gigs for working players to back American jazz musicians stationed in Japan. Given the racially segregated bases and differing tastes among the troops, Japanese musicians had to hone both chops and flexibility. For all the variety and influx of current American jazz into the ether, a musical identity crisis was brewing among Japanese jazz musicians.

Things evolved in the 50s when Oscar Peterson was touring Japan and discovered a prodigious young pianist who’d become an early hero in the Japanese Jazz scene: Toshiko Akiyoshi. A virtuoso player and composer, she challenged the patriarchy and insisted on sticking to her guns and playing the bebop she loved rather than what she was expected to play. Akiyoshi became the first Japanese student in the US at Boston’s Berklee School of Music (on a full scholarship). She’d become one of jazz's most influential players, composers, and arrangers. Now 94 years old, she’s earned global critical acclaim and was awarded the title of NEA Jazz Master in 2007. For this brief history, Akiyoshi was among the first to add unique Japanese timbral facets and instrumentation to the bebop, swing, and emerging hard-bop jazz stylings that Japanese musicians had mastered. Akiyoshi was a bold pioneer in demonstrating that not all jazz had to remain in copycat mode.

Other names, such as Sadao Watanabe, would follow in Akiyoshi’s wake as the groundswell of jazz popularity continued to increase. Given that imported jazz records (and home stereos) were scarce and expensive, listeners flocked to jazz kissa in order to get their jazz fix. These small cafes served alcohol or coffee (or both), sported quality stereo systems, and enviable album collections. Patrons could spin the latest records while enjoying a drink, often in a small setting. The jazz kissa grew from a handful in the pre-war era to HUNDREDS throughout the country. And just as jazz was going through changes in the USA, a new generation of Japanese musicians were eager to experiment with new sounds and challenge (or expand) existing jazz forms. By the end of the 1960s, jazz in Japan had absorbed and transmogrified sounds, timbres, and variations that kept one foot in the form's roots yet had a sound all its own.

…and Algorithmic Mystery

What is it about the sound of Japanese Jazz that feels the same yet different? Why are so many people spanning a broad swath of music tastes stumbling across it from seemingly random places yet loving what they hear? A significant example is Ryo Fukui’s Scenery, which has logged over 13 MILLION streams for no discernible reason. I’ve spent much time looking at YouTube analytics for an answer. If you read through the comments, you’ll see that people seem to have NO IDEA why this record was recommended to them, but everyone seems to fall in love with it. Go figure.

J-Jazz Escapes the Niche

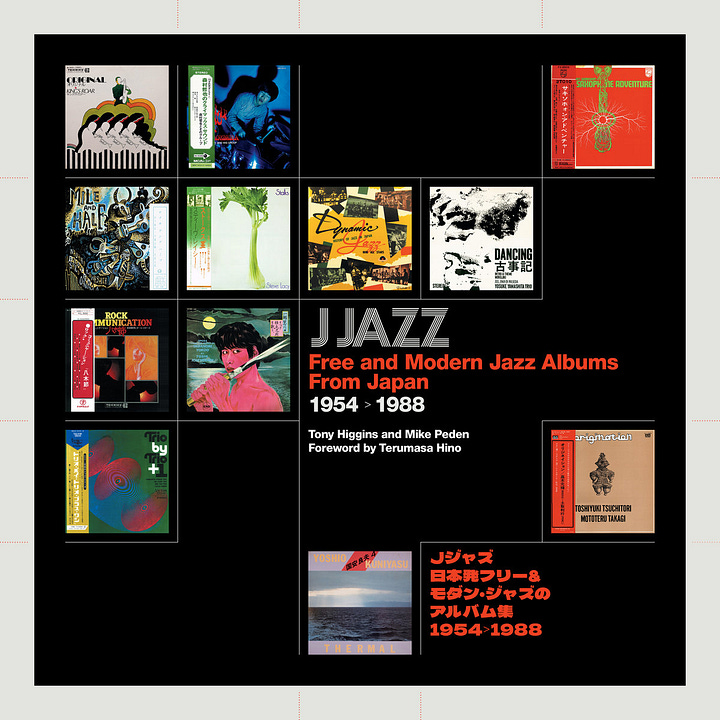

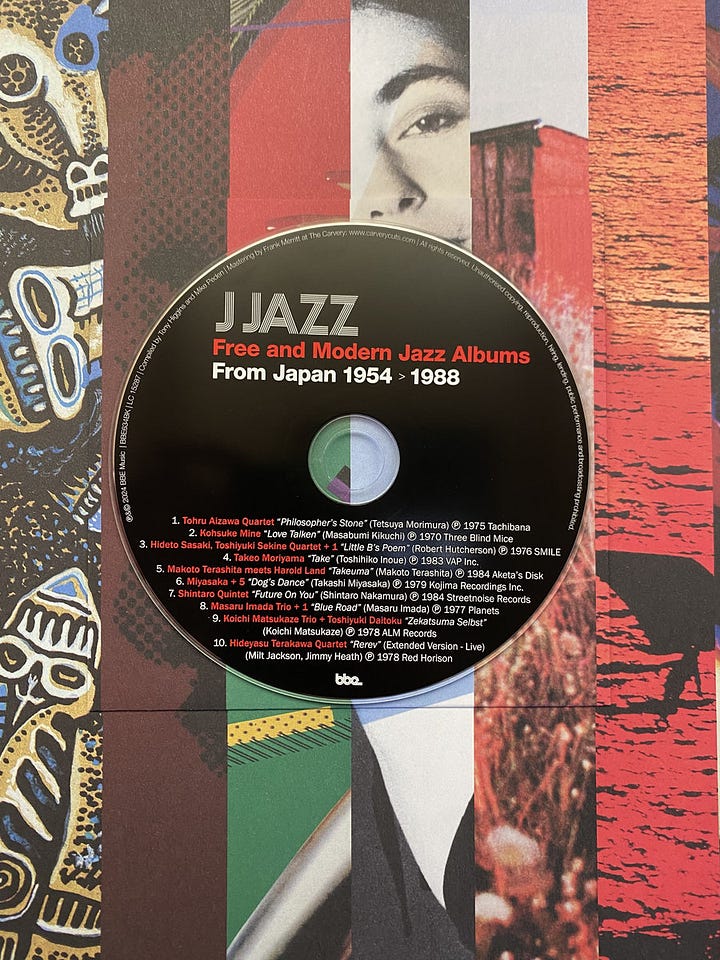

Japanese Jazz (J-Jazz going forward, for brevity) has been a gift that keeps on giving. Since 2018, Tony and Mike have overseen three more J-Jazz DMJFJ compilations and launched the J-Jazz Masterclass series for the BBE label. But they’ve REALLY done it this time—the coffee table book (and accompanying CD) that just landed here is a work of art with storytelling that reveals the history and mystery of J-Jazz like never before. The book and liner notes do a thorough and fascinating job of telling the story of J-Jazz—tales that enhance the listening experience.

They say size doesn’t matter, but it’s over 300 pages of text and BEAUTIFUL reproductions of album cover art. This gorgeous and impressive book references over 500 albums plus editorial and favorites/top lists from multiple jazz personalities. I’ll be pouring over it for months, referring to it for years, and enjoying it for a lifetime—it’s terrific. It’s also repeatedly sending me downstairs to the J-Jazz shelf, which is good—never skip leg day! And it’s timely. I attended a wedding last week where I waxed enthusiastically about J-Jazz to my pal Craig, and he wanted recommendations. So here are a few of my favorite J-Jazz records:

The J-Jazz: Deep Modern Jazz Series

Here are three tracks from J-Jazz Volume 1: Deep Modern Jazz From Japan 1969-1984—a triple album of utterly captivating music. It’s a great entry point into J-Jazz and has tremendous staying power. The curation here is some of the best I’ve ever seen on a jazz compilation, and the attention to detail — the obi, the detailed insert, the writing, the fact that the VINYL version has the bonus tracks — is a lesson in craftsmanship. You’ll hear strong writing and killer performances that range from fusion-inflected post-bop to trios, quartets, and quintets rooted in modal, blues, and hard-bop traditions to spiritual jazz flights into the cosmos. All killer, no filler. And this is just V1—wait until you hear the NEXT three volumes!

Enter the Dragon Dance: The J-Jazz Masterclass Series

Topology is the fourth release in the J-Jazz Masterclass Series via Barely Breaking Even Music, a series also curated by J-Jazz experts Mike Peden and Tony Higgins. Tenor sax legend Harold Land cut this gem in June 1984 with pianist Makoto Terashita, bassist Yasushi Yoneki, percussionist Takayuki Koizumi, and drummer Mike Reznikoff for the obscure Aketa’s Disk label in Japan. The opening track, “Dragon’s Dance,'' immediately sets the tone with a captivating piano workout from Terashita that evolves into a full-band modal/spiritual journey that, at twelve glorious minutes, STILL feels too short! The chemistry between the veteran Land and relative newcomer Terashita is evident throughout. While echoes of Land’s hard-bop and West Coast roots are present, the sound here leans modal, with Land wearing some John Coltrane influences on his sleeve. Props to all involved with this reissue cut at 45RPM across two LPs for maximum fidelity, housed in a high-quality jacket with an obi and FANTASTIC liner notes.

Kiyoshi Sugimoto: Fretboard Fusion Frenzy

Guitarist Kiyoshi Sugimoto is a familiar name in the J-Jazz scene. Sugimoto is an in-demand player whose name appears on dozens of records as a sideman, and he’s led many of his own. His style spoke to me immediately, with a deft touch and willingness to bend and blend genres to make his solos unique. Two of his records as a leader cry out to be heard: Country Dream and Babylonia Wind. One evening while listening to the title track of Country Dream, my brain connected it to something I’d played while on the go earlier that day—the Grateful Dead’s “Here Comes Sunshine” from 12/19/73 (Dick’s Picks Vol 1). I’m not a musician, but I consulted the family expert who pointed out Sugimoto’s “Country Dream” is in A minor, and Garcia is developing his solo over C major. If you play the songs back-to-back, you’ll hear the connection.

Rare ≠ Quality. Except When It Does.

One of the commonalities of many early J-Jazz records was the small pressing runs, which not only limited the audience but also created collector’s items that now go for comically huge money. Experienced collectors have learned (often the hard way) that scarce records can take on a near-mythical status, and assuming a correlation between rarity and quality of music can be an expensive mistake. But sometimes, a rare record delivers the goods and then some. Case in point: the Masao Nakajima Quartet’s Kemo-Sabe record has eluded many collectors for decades. However, the excellent reissue reveals a record that lives up to the hype. If the title track doesn’t get you, the rest of the album will!

Go Big or Go Home

Toshiyuki Miyama & The New Herd’s Tsuchi No Ne quickly made my Best of 2021 list, packing a sonic wallop so humongous it scared the neighbors. This is big band prog fusion Avant monster movie car chase Kung Fu music. Got that? WILD record. Kevin Gray cut this beast of an album and got every possible sound out of each groove. Before spinning this one, wear protective clothing and a crash helmet, and leave your assumptions at the door. If you’re looking for a tidy big band record with identically dressed, clean-cut lads delivering dance music for dinner clubs, prepare for disappointment. And if you like your big band jazz smooth, relaxing, and mellow, you’ll hate this.

Musicianship Takes Flight

Great Harvest is pianist Makoto Terashita’s debut, recorded in New York on 3 June 1978 with a band of US and Japanese musicians that includes Errol Walters (bass), Jo Jones (drums), Bob Berg (tenor sax), and Yoshiaki Masuo (guitar). Musicianship takes point throughout this record, and while it’s not grandstand-y or showoff-ish, these players have come to play and enjoy filling in the blanks. I think the virtuosity suits the music perfectly, and nobody overdoes it. The atmosphere sounds fun, which adds to the enjoyment of listening. There are three originals by Terashita, highlighted by the 10+ minute “Tell Me An Old Story, Grand Papa.” The quintet digs into the swing on two standards: Monk’s “Ruby My Dear” and Ellington’s “Take The Coltrane.” The sound on this recording is excellent, and reissues are plentiful in the marketplace.

Kohsuke Mine is a J-Jazz legend with many terrific albums to his name. Daguri is a high-energy, modal/spiritual face-melter of a jazz record that packs quite a punch. Fans of McCoy Tyner’s early 70s Milestone records will go apeshit over this. Kohsuke Mine handles tenor and soprano sax and is the composer of all five mid-to-long tracks on Daguri. He’s joined by Hideo Miyata (tenor sax), Fumio Itabashi (piano), Hideaki Mochizuki (bass), and Hiroshi Murakami (drums). The opening track is molten intensity, as the saxes and piano intertwine and build the tension, somehow digging the groove deeper while soaring higher. They dare one another to keep up, and the challenge is accepted as each peak is reached and transcended. The drum and piano work throughout moves from intricate to manic to hyperactive—the first track alone will leave you breathless and reaching for another coffee. But the instrumental highwire act never steps on the tunefulness—groove, swing, and virtuosity co-exist in ideal proportions on every track. Only one tune, “Self Contradiction,” is on the downtempo side. Otherwise, you should set the gearshift for the high gear of your soul! These performances are lethal, but who said great jazz was safe?

Final thoughts:

To those coming to jazz from the prog-rock or jazz fusion realms (as I did), one of my key “gateway bands” was a Japanese outfit called Kenso. They’re led by Yoshihisa Shimizu, a badass guitar player who wears a white medical-style lab coat on stage—he’s a dentist in Tokyo by day. It makes sense that I’d slow my scroll when I saw the headline about the Japanese medical student, right? Kenso was an instrumental combo that formed in the 1970s, performed on and off through the 90s, and is mainly dormant these days. They made a consistent run of strong records that blended Brand X, Pat Metheny, Return to Forever, and Bruford influences. They’re strong players, and the writing is good, with plenty of strong melodies. They remain in rotation. Kenso II is my favorite studio record. They have a TON of live albums. Two see more play than the others here: Ken-Son-Gu-Su, their 25th Anniversary concert, and Music For Unknown Five Musicians from 1985 when they were young, hungry, tight, and playing with molten intensity.

As I head to the J-Jazz shelf again, I know this list is just a handful of top-of-mind examples. I could go on and on, and I may do so again at some point. While I’m no longer a beginner, I have a long way to go before I achieve J-Jazz expertise. But there's no shortage of resources to explore between ongoing compilations & reissues, Mike and Tony’s fantastic new book (Dusty Groove link for US buyers), and excellent writers here—such as Brian McCrory’s outstanding Jazz of Japan Substack.