Just when you think the great ‘analog vinyl vs. digital music’ war has finally gone underground—left to be fought by basement-dwelling warriors with way too much skin in the game—the New York Times drops a HUGE piece on Chad Kassem and Analogue Productions.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m pleased for Chad, and the article speaks well about the continued health of vinyl, reissues, and the hobby we all enjoy. Within minutes of this article going wide, my inbox lights up. Again. There’s a perpetual curiosity about which format (or listening experience) is superior. In general, when it comes to these kinds of debates, it’s all good fun. Plus being “right” is overrated—it’s just social bragging points when one side or the other scores a perfect zinger. However, whether the debate gets hot again due to a mainstream press piece, or I start to feel guilty about the unanswered questions piling up in my Inbox, I feel like I’ve been drafted into a war I didn’t enlist for. Do I think vinyl is “better” than digital? Do I have a preference? What do I recommend?

The answer to all three is the same:

It depends.

A Day in the (Get a) Life

Like politics or religion, analog/vinyl zealots—not enthusiasts, but those a step away from full-on Luddite mentality when it comes to digital—seek any opportunity to make their case. Recently, I had the good fortune to receive an invite to a private listening session for a well-known album that was getting “the treatment” with a full-blown remix, remastering, and all the bonus trimmings. The playback was on an excellent-sounding digital system. I was fully locked in—head nodding, hands air-guitaring, lost in the music.

Then: a jab in the ribs. A stage whisper thick with Miller Lite:

‘Have you heard this on vinyl?’

I’m a peaceful person, but if I had a portable lathe, I would have started cutting his eyeball like a lacquer. He continued pontificating. “This sounds so clinical! So cold! I mean, you can hear the music much better, but there’s no soul in the sound!” At that moment, I inwardly sighed: vinyl snobs are the concert snobs of recorded music. Nobody likes those guys, standing cross-armed with a disapproving look, sucking all the fun out of the club. Vinyl snobs are no better and often worse. The music usually drowns out the concert snob. The vinyl snob is frequently more audible, so you can hear him pulling the pin from every grenade of absurdity.

Vinyl snobs love to dish it out, but they must take it, too. They’ll be showing off their collections and fancy gear to a room of friends. As they spin records attempting to point out the sonic nuances of analog superiority, trying to drop the stylus with PERFECT precision in just the right place as the pile of records they’ll need to reshelve grows, a heretic’s voice emerges from the pure, analog din:

“Man, I don’t get it. Digital is so much more convenient and sounds just as good. Vinyl is just a nostalgic fetish preying on manufactured FOMO in the name of consumerism.”

Suddenly, the room clears—except for Analog Asshat and Digital Douchecanoe, now locked in an audiophile Thunderdome. Two nerds enter. One nerd leaves. (Eventually.) But only after the world’s most pathetic hand-to-hand combat, where the real casualties are logic, nuance, and any chance of getting laid.

But here’s the thing: this fight isn’t about sound quality—at least, not entirely. It’s about our relationship with music, and how we value our time. It’s about experience, psychology, and expectation bias. And if we can stop obsessing over waveforms, bass roll-off, and vertical tracking force for a moment, perhaps we’ll agree that analog and digital formats serve different—but equally valid—purposes.

Has Audio Gotten Worse? Has Our Vision Improved?

Before we get to the vinyl vs. digital debate, let’s talk about something no one likes to admit: audio quality has lagged embarrassingly behind video. That’s why high-end audio has gone from a niche hobby to a desperate course correction. Note that I didn’t say advances in audio, which was the canary in the coal mine as far as compression technology and the entertainment business are concerned.

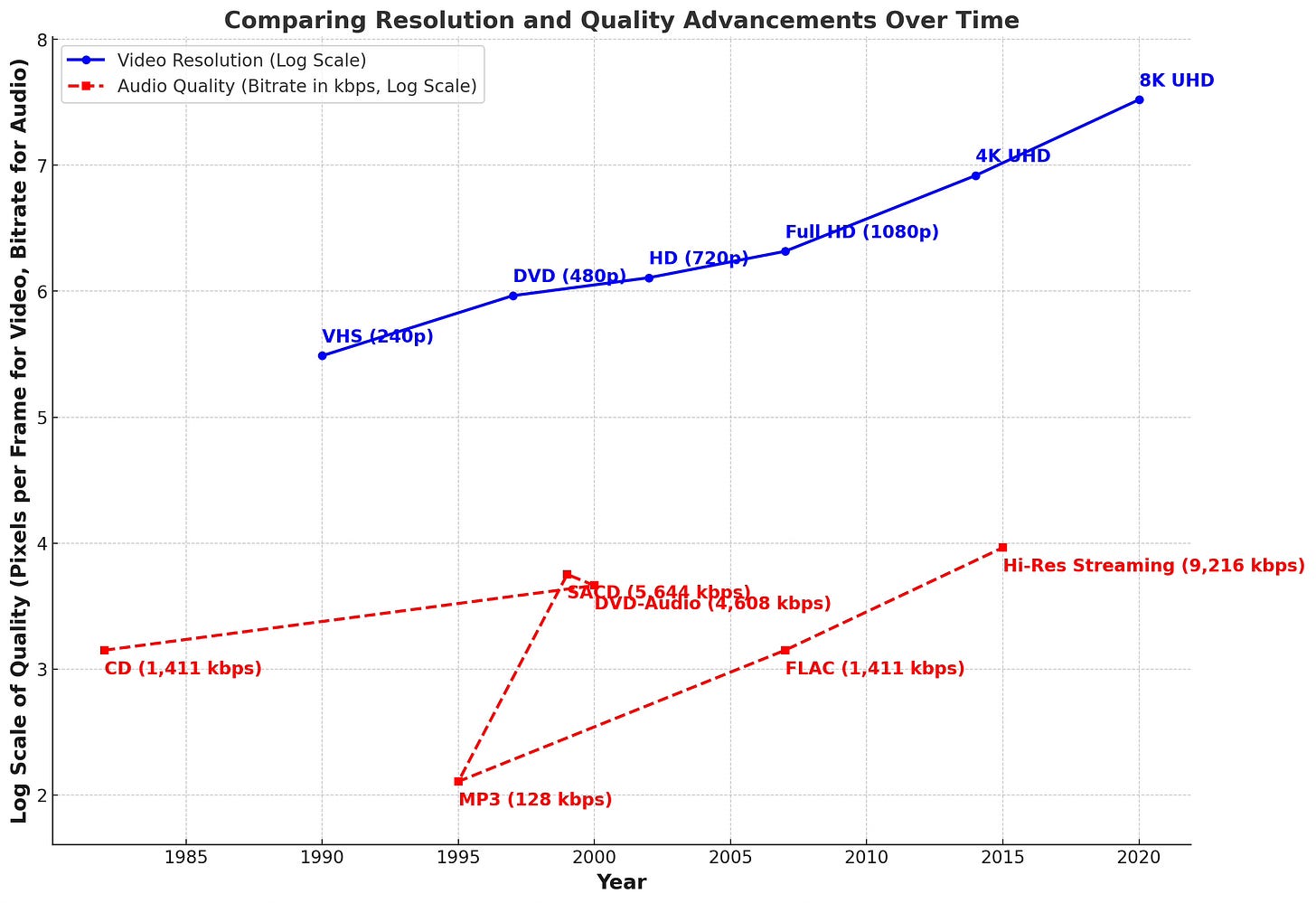

There was a MASSIVE leap in video quality versus incremental gains in audio quality from the mid-80s until now. You don’t need to be a tech guru to look at television from the 80s against any modern LG or Samsung you’d find at Best Buy to see a dramatic improvement. Even if I play loose with the numbers, the leap from VHS to 8K is ~300K pixels per frame to over 33 MILLION, a ~100K jump. In contrast, audio advances from CD to High-Resolution Streaming, 1,411 kbps (CD) to ~9,216 kbps. A 6X increase in audio fidelity is noteworthy, but it’s much less perceptible.

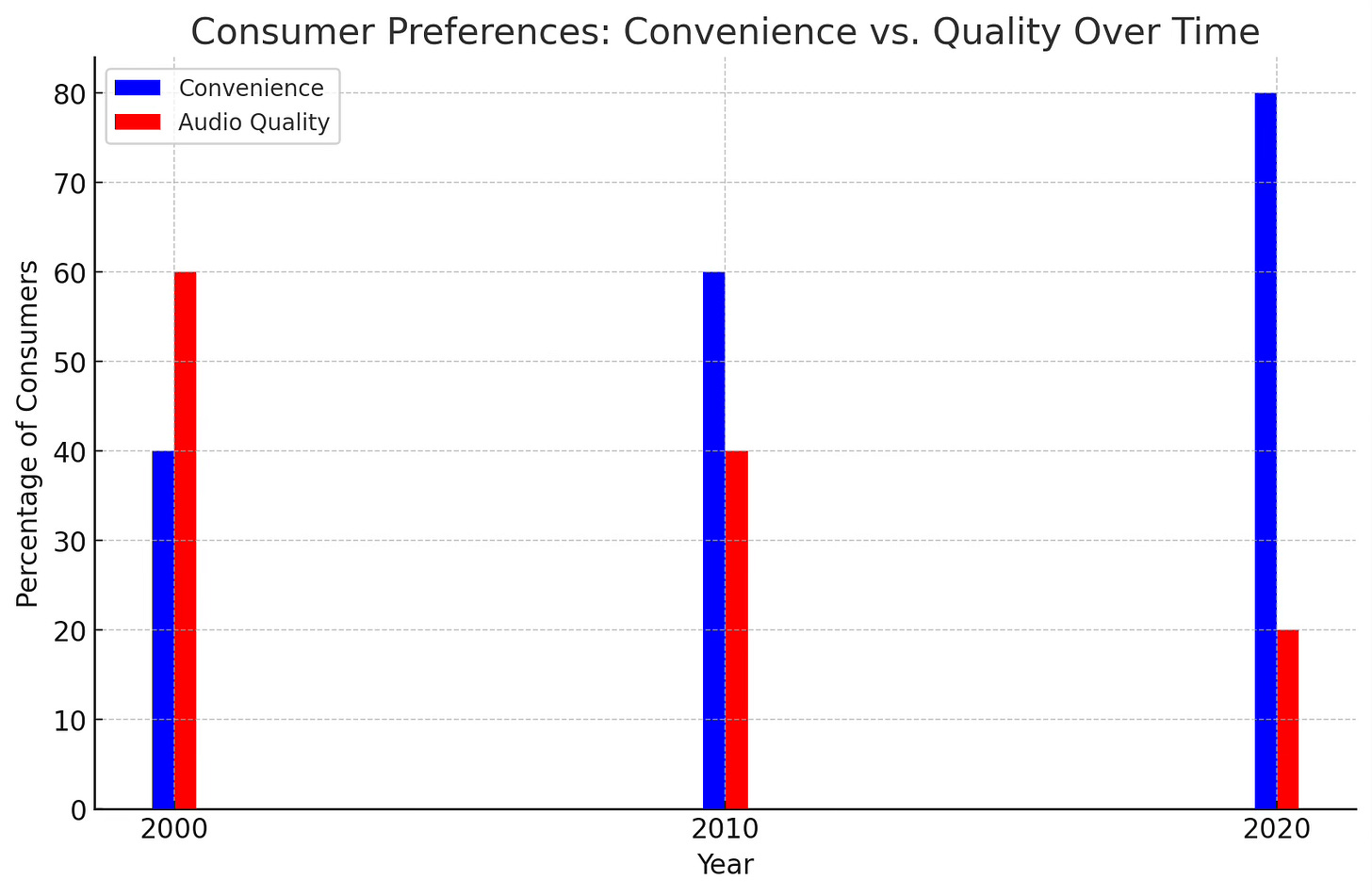

Video also enjoyed a smoother technological evolution, backed by deeper pockets and better marketing. Audio had longer periods of stagnation, and the MP3 interregnum, which was marked by legal wrangling, distrust, and the rise of the iPod. Apple’s personal audio invention became a nearly ubiquitous consumer electronics device that convinced many that trading fidelity for convenience was a net positive. The iPod also trained an entire generation of ears to adjust and live with the compromises of compressed, lower-quality audio.

The ongoing improvements to the iPod rarely touched on better fidelity—it was about holding MORE music, not better-sounding music. The marketing was about having your entire collection in your pocket—how convenient!

While vinyl was at its lowest point in the early 2000s, the format began a slow but steady resurgence—one that’s since become a cash cow (and a headache) for record labels in ways they never saw coming. As veteran collectors basked in their “I told you so!” moment, former CD loyalists came crawling back, and a fresh wave of vinyl converts emerged. Some inherited stacks of records already collecting dust at home, others got hooked through DJ culture, and plenty just needed a hobby while bored out of their skulls during the pandemic. And with that, the analog vs. digital war reignited—this time, supercharged by bad-faith arguments, revisionist history, and the bottomless pit of online know-it-alls.

Vinyl’s Superpower: The Ritual of Listening

If there’s one thing vinyl purists agree on, it’s that records force you to listen differently. You can’t shuffle vinyl like a playlist, and absent a full-time vinyl sommelier, no algorithm will make a selection from your library and deliver it to your turntable by drone. The rite of considering the appropriate music for the moment, placing it carefully on your deck (after cleaning it, because you DO clean your records before playing them, right?), and pouring over the artwork with reverence and awe are part of the listening experience. It’s tactile, deliberate, and immersive. It’s listening with intent.

This isn’t just audiophile snobbery. There’s a growing body of psychology studies around how physical engagement with music enhances the emotional connection because our brains link sensory input to memory and pleasure. For some <raises hand>, handling records—placing the needle, flipping sides, scanning the credits—creates a kind of musical mindfulness that’s hard to replicate with a streaming service. I’ll go out on a limb and claim that shopping for used records creates a similar mindfulness. Go ahead and prove me wrong.

That mindfulness is like giving yourself a license to immerse yourself and enjoy a lengthy trip through artwork that’s a LOT easier to enjoy in a 12” X 12” format. As one who toils over writing liner notes to get them exactly right, the larger album format makes them more legible. Plus those deluxe gatefolds came in handy YEARS before the digital music revolution—a revolution that forgot a significant listening augmentation. If you’ve ever tried removing stems and seeds with a playlist, you know what I mean.

At the end of the day (which seems to be the only time when anything happens in the music industry), all-analog vinyl is to music what wood-fired pizza ovens are to cooking, adding craft, artisanal spin, unique nomenclature, and ultimately a license for artistic imperfection that makes the result more human. Some listeners hear it, some don’t. Some hear it more dramatically than others. Others struggle to listen to music that doesn’t have that particular sonic quality.

Digital’s Superpower: The Democracy of Access and the WOW! of Convenience

For all the romance of vinyl, digital wins the science fair.

If you want to talk about science you can’t hear, we can get into bit rates, resolution, noise floor, and inner groove distortion. I apologize to the handful of fruit bats I’ve just offended, and if bat jazz combos are killing it above 20kHz, I’m jealous of your hearing.

But the real victory? Convenience. Digital lets you carry the entire history of recorded music in your pocket. It gives artists worldwide reach without needing pressing plants, warehouses, or shipping costs. And let’s be real—most people aren’t listening on $10,000 hi-fi systems. If you’re playing music through AirPods or a Bluetooth speaker, vinyl’s sonic advantages evaporate pretty quickly.

It’s a lot more than that though. If you’re of a certain age <raises hand again>, you probably still mentally and physically organize music by genre. That’s one of the first identifying characteristics of a digital migrant. Digital natives—those born in a post-MTV TRL era who’ve always known a world with iTunes or streaming—prioritize context over genre. When or for what purpose they’re listening to music is more important than what “type” of music it might be. So “Morning Commute,” “Afternoon Focus,” “Arm Day Workout,” and “Wind Down” playlists may contain a blend of genres. One breakup playlist can be hopeful, sad, and angry, with Rory Gallagher, The Ting Tings, and Erykah Badu happily cohabitating.

A well-considered digital approach goes even further. Returning to my affinity for liner notes and credits in an album, some platforms (I’m looking at you Qobuz and Roon) create the kind of music discovery rabbit holes that have (seemingly) no bottom. I have a sizable local digital library that Roon has cross-indexed. This means that when I’m enjoying the CSN Box from 1991 (still one of the best-ever music boxed sets ever), I can access a level of detail impossible to achieve with vinyl. Furthermore, I can see (for instance) how many other versions of “Deja Vu” are in my library, and the software scans for (and reminds me) of performances of that song by others I may not know, along with other related music which gets me listening outside my usual lanes. That example led me to guitarist Fareed Haque’s CSN covers album, which I haven’t listened to since catching him live with Garaj Mahal twenty years ago.

You knew there had to be a “but” coming. Most digital listening happens in lossy formats (MP3, AAC, Spotify’s 96kbps abomination, as if folks needed another reason to complain about Spotify), which algorithmically discards “unnecessary” bits of original audio data and your brain fills in the blanks. In other words, the average streaming listener has never heard what well-mastered, high-resolution digital music sounds like and can achieve when done well.

One way of looking at it is that digital is like a library card granting access to every book ever written; vinyl is the first edition of a treasured author. One prioritizes breadth, the other depth. Each has its charms, each has its shortcomings. Both, when done correctly, can make magic. Co-existence is within reach for those willing to stop treating this debate like a winner-takes-all deathmatch, and forget about being “right.”

Digital music offers convenience, portability, vast access, flexible listening options, and excellent fidelity with proper setup. Vinyl offers immersive, tactile engagement that leverages the emotional resonance of music more mindfully. Vinyl’s unique audio qualities can’t objectively be called “better,” but it is subjectively more satisfying and authentic to many listeners—even if such reports can’t be scientifically corroborated. Yet.

We convince ourselves that specific formats sound better because we want them to. That’s why blind A/B testing routinely exposes audiophile delusions. Case in point: There’s no shortage of hypotheses and anecdotal evidence about listeners rating music higher when they’re told the system is expensive, even with the same audio. I’m not one to tell anybody how to lead their lives or spend their money. But will an $850 carbon fiber record brush make anyone’s album sound audibly better than the $25 off-brand brush I use from Amazon? At that point, I have to wonder if audiophilia has crossed over into a dick-measuring contest for the uber-wealthy.

What Chad Kassem & Analogue Productions Get Right

The recent New York Times piece on Chad Kassem and Analogue Productions underscores one of the biggest misconceptions about the vinyl resurgence: It’s not about nostalgia—it’s about curation. Kassem’s company doesn’t just press any old record. They meticulously source analog masters, work with the best engineers, and package everything with museum-level craftsmanship. It’s not just about sound—it’s about experience.

And that’s the real takeaway here: People will pay for an experience. Whether it’s vinyl, a live show, or a high-res digital master, the format doesn’t matter as much as how it makes you feel.

A Manifesto for Happier Listening

1. Define Your Goal → Ritual (vinyl) and exploration (digital) can co-exist. Really.

2. Test Before You Invest → Listen to music, not gear. Use ABX testing apps to challenge your biases.

3. Prioritize Music Over Gear → If you spin on the run and at home, give thought to a balanced digital/analog setup. You don’t want to be happy with music only half the time.

At the end of the day?

The best system isn’t the one with perfect specs—it’s the one that vanishes, leaving only the music.

Until next time…

“Analog Asshat and Digital Douchecanoe” will have me laughing all day 😆. Also, I’m with you. Vinyl, cassettes, cds, and streaming all have a place in my listening universe.

Well-written piece. I've become more format agnostic during recent years, provided whatever my choice is sounds good (or at least brings me pleasure). Vinyl, CDs, and streaming (TIDAL) are my typical options, each with their own appeal. I enjoy vinyl in part because it forces me to slow down and to interact more with the physical media. I have both audiophile pressings and other LPs that have seen better days. CDs are most often listened to in the car, and streaming is mostly done when I'm at the office (though I do listen to both at home sometimes).