My debut Substack post, when I launched the Jazz & Coffee Substack, was Feelin’ Good About Hank Mobley. In honor of his 95th (heavenly) birthday today, I’ve decided it’s time for a rewrite and an updated look at Mr. Mobley’s music.

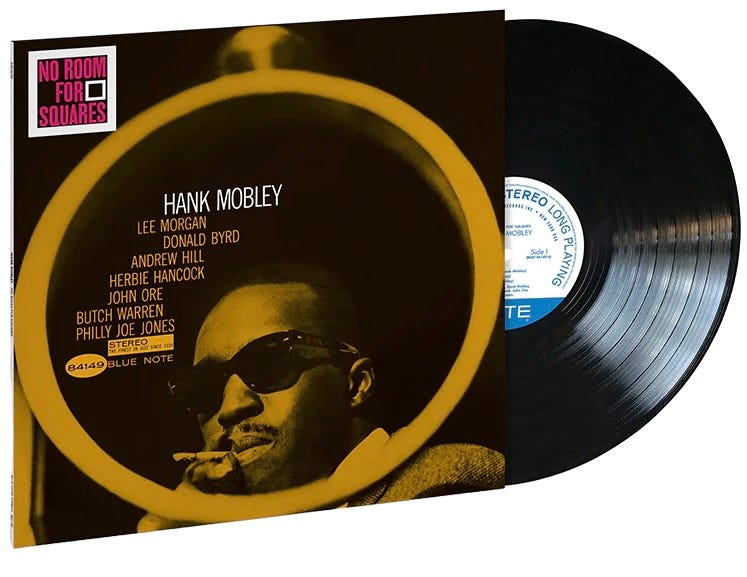

No Room for Squares inspired my initial post, and the music on this record continues to inspire me. As well as the photo on the cover. And what a great album title!

One of the most compelling aspects of Hank Mobley’s work is its accessibility. His compositions and recordings offer immediate appeal, even to listeners with limited exposure to jazz. This isn’t to suggest Mobley’s music lacks depth or sophistication. Mobley may not have redefined the instrument like Coltrane, advanced harmonic language like Shorter, or shifted stylistic boundaries like Rollins. However, Mobley’s melodic clarity, structural coherence, and rhythmic phrasing reflect a mastery that rewards close attention. His music becomes even more compelling when placed in the proper historical and artistic context.

No Room For Squares heralds the start of Mobley’s third and final burst of artistry based on the three broad phases I use to subdivide his career:

Triassic Mobley

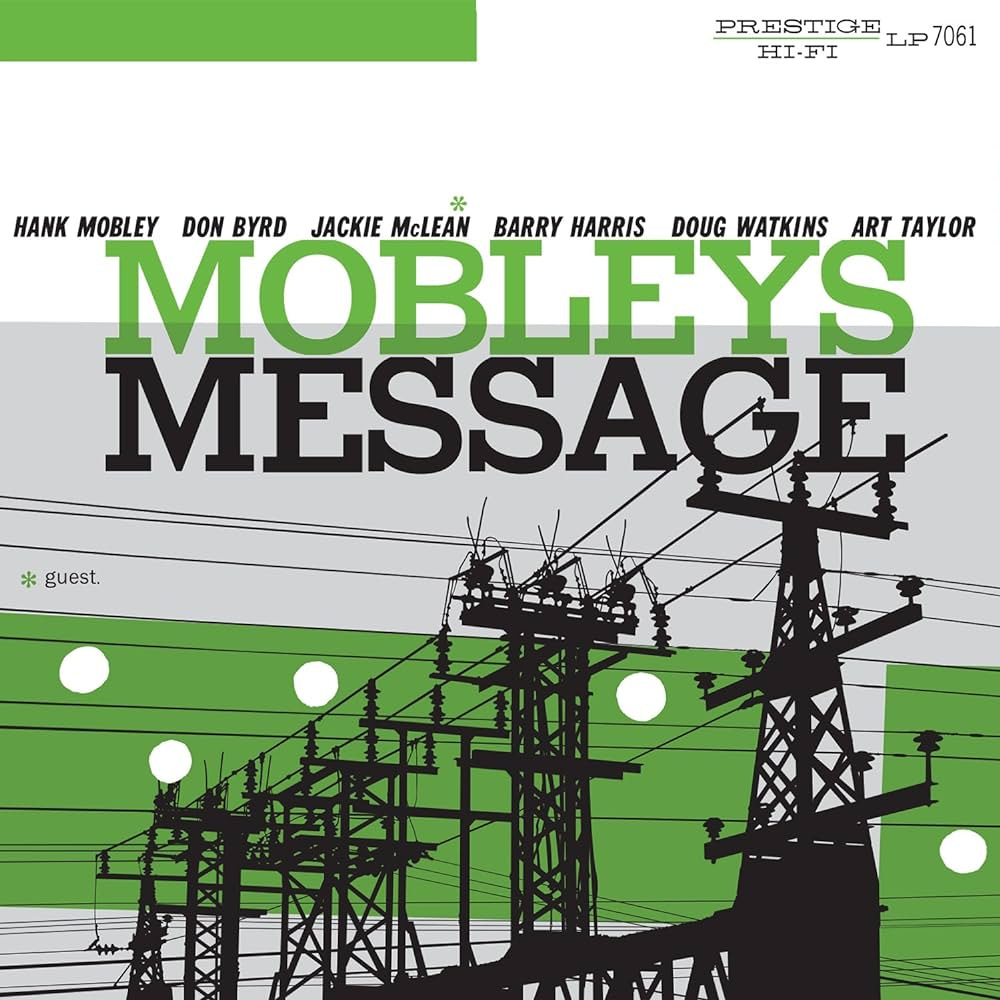

Mobley’s career begins with his first recordings under Max Roach’s leadership in 1953, through the formation of the Jazz Messengers and the nine albums he recorded as a leader for Blue Note, Prestige, Savoy, and Roulette between 1953 and 1958. It was during this phase that Mobley began dabbling in narcotics, leading to his first arrest and incarceration. It wasn’t the last: Mobley’s addiction issues would drag him down repeatedly throughout his career.

Jurrasic Mobley

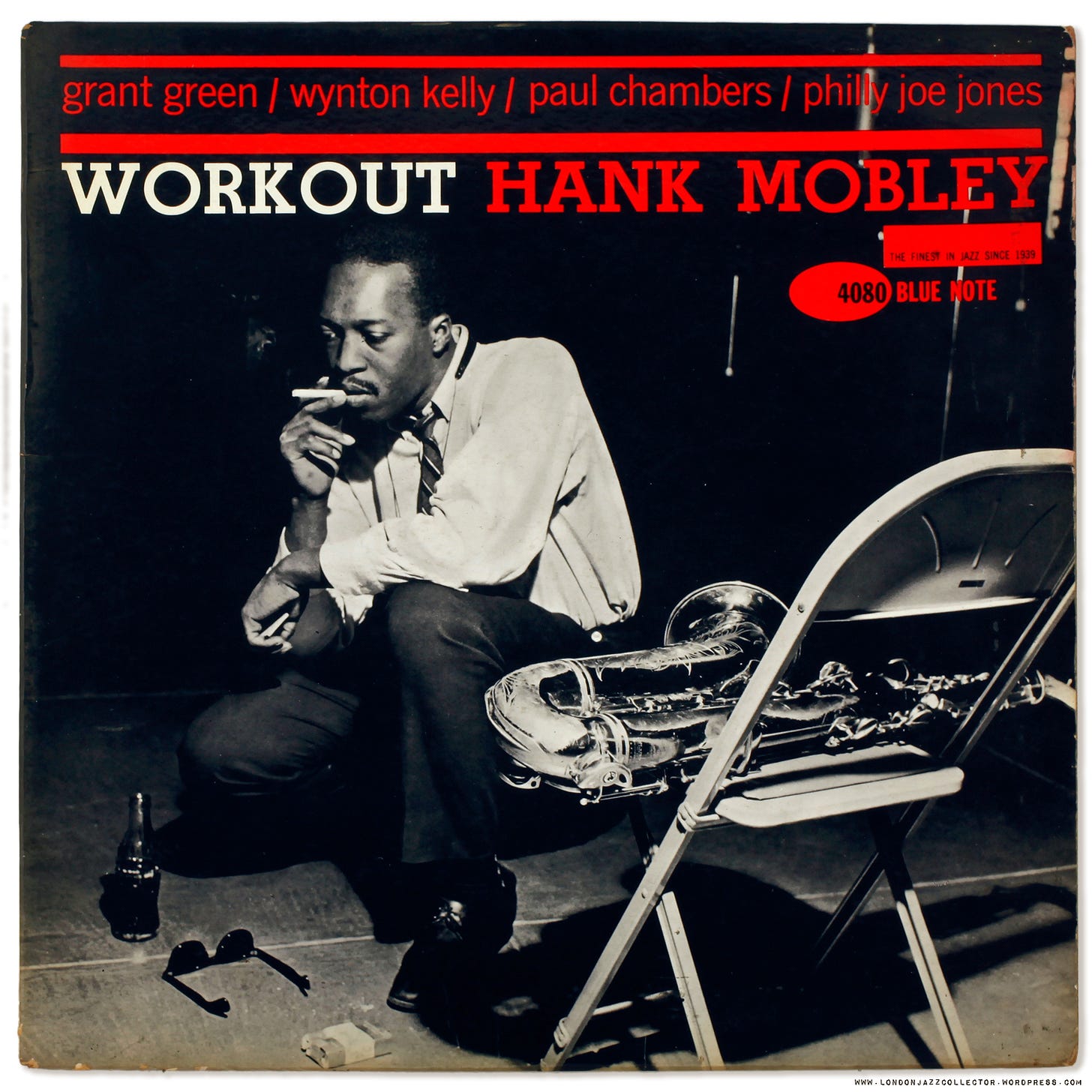

Mobley left prison in 1959, reconnecting with his mentor, Art Blakey, and woodshedding with the Jazz Messengers to get his chops back in shape. Once he’d regained his sea legs, Mobley’s creative muse came calling to catalyze his “main sequence” of recordings: four albums that remain among his best and most revered work. Roll Call, Workout, Another Workout, and the iconic Soul Station are all hard-bop classics.

Soul Station is one of the first jazz CDs I ever bought and remains on my short list of recommendations for those looking to build a jazz library. It’s one of the records I turn to when someone tells me that they’ve struggled with one of the other usual suspects from the “beginner” jazz records lists, and I have yet to recommend it to anyone who hasn’t liked it.

In addition to leading this impressive run of albums for Blue Note, Mobley was invited to join Miles Davis and lend his tenor skills to Someday My Prince Will Come, and Miles’s live sets At the Black Hawk and At Carnegie Hall. However, Mobley’s stint with Miles Davis was far from a dream gig. Whether Miles always saw Mobley as a temporary placeholder or Mobley never picked up on what Miles expected of him is a long-running debate. What’s clear is that Mobley was guilty of two crimes:

Not being John Coltrane or Sonny Stitt (whom he replaced)

Not being Wayne Shorter (who Davis wanted, but couldn’t get, yet.)

The notoriously impatient Miles began hazing Mobley like any new band member. Still, as Miles’s frustrations increased due to Mobley’s inability to give him exactly what he wanted, his behavior towards Mobley grew progressively more mean-spirited. Mobley’s skin could’ve been thicker than the fat layer on the high school cafeteria meat loaf, but it was no match for the relentless taunting from Miles. Despite Mobley’s place in the foremost jazz combo of the day and leading the most robust sessions of his career, his confidence began to erode. Depression, despondent, and demoralized, Mobley's weariness of others’ expectations drove him back to the needle and spoon.

Jurrasic Mobley was a short, productive epoch that yielded some of Mobley’s most renowned music, but it ended on a troubled note—addiction and prison beckoned once again.

Cretaceous Mobley

Incarceration, drug addiction, and trouble with the law kept Hank Mobley off the radar for most of 1962. While he was behind bars or struggling to get clean, he was licking his wounds from his Miles Davis experience. Though Mobley must have found it difficult to find silver linings from that Miles era, it’s undeniable that his musicianship and compositional skills evolved under pressure. His writing began to embrace the modalities Miles pioneered with Kind of Blue. Mobley’s “middleweight” style became rougher around the edges, with emotional bursts of notes that emphasized registers at the high and low ends of the horn. His approach also began integrating tension & release building blocks, while his phrasing was less predictably behind the beat. Ironically, these shifts in Mobley’s approach nodded to Coltrane without stealing his licks or blatantly copying his style. This stylistic upgrade adds a special touch to Mobley’s final run of albums, which are now (finally) receiving a long-overdue reevaluation.

No Room For Squares combines parts of two sessions from 1963, with the remaining tracks from those sessions scattered across other releases or issued as bonus tracks on CD.

If you can find it reasonably priced, my favorite way to enjoy the March 7 session is through the Music Matters release, The Feelin’s Good. Music Matters produced a stellar run of audiophile Blue Note reissues that will stand the test of time and laid the groundwork for the Tone Poet series. The Feelin’s Good is a custom-crafted Music Matters release with the same spirit and vibe of a classic BN record. It is long out of print, and as great as it sounds, the second-hand prices are ridiculous. If you want to hear this March 7 session as sequenced, here’s a lossless (and Hi-Res) digital edition as a Qobuz playlist:

The Feelin's Good Qobuz Hi-Res/Lossless Playlist

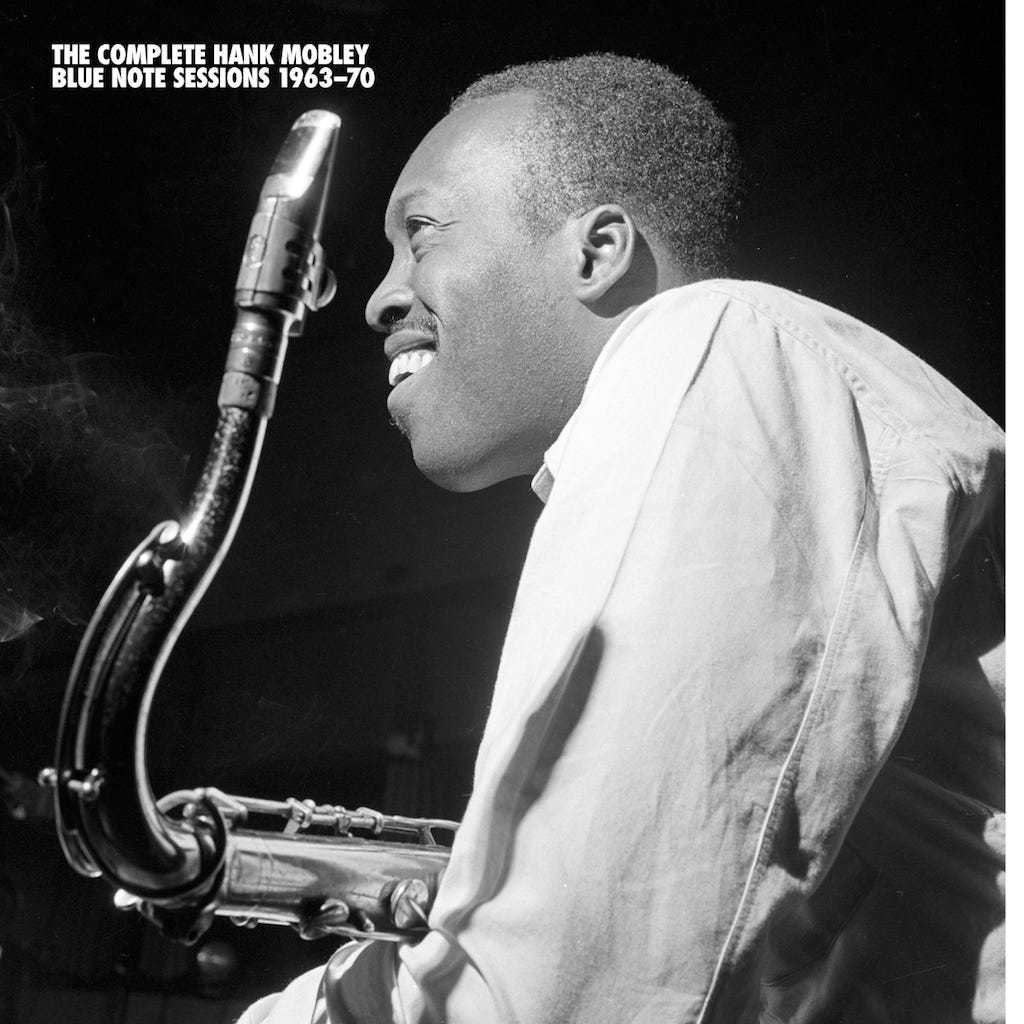

For those who aren’t married to vinyl, the optimal digital edition is the Mosaic Box, The Complete Hank Mobley Sixties Sessions 1963-70, which includes not only everything here but also a couple of alternate takes and all of Hank’s FANTASTIC 60s work. The mastering by Malcolm Addey is terrific, and as with all Mosaic boxes, the liner notes and photos provide a great deal of depth and context. It’s out of print, but it's worth every penny if you find a copy.

Scattered across several albums, Mobley’s final epoch was marked by a flurry of increasingly interesting compositions and musically deep sessions that Blue Note would produce, vault, and then issue partially and/or posthumously. Some were released as intended, while others were added as bonus tracks to CD reissues or compiled into entirely new albums, as they had no other home. Mobley’s frustration with Blue Note’s approach increased until the notoriously press-shy Mobley erupted in anger during a rare interview, expressing a ginormous WTF as to why Blue Note kept asking him to record when they seemed to have little intention of ever releasing the half-dozen records he’d already given them!

Blue Note put lots of mid-60s sessions on ice: Mobley had plenty of company across the roster, from the less-commercially inclined Andrew Hill to hitmakers like Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter. That was little solace to Mobley, who remained bitter about this stranglehold over his music until the end of his days. It’s easy to see his point as the quality of his final run of albums was consistently high. There’s much to explore on Thinking of Home, Third Season, and A Slice of the Top, which remain three of my favorite Mobley records. The latter two have received the Tone Poet treatment, so it’s reasonable to expect that Thinking of Home will be right behind it, but first, dig into No Room For Squares.

It’s the best album from the least-discussed but most-rewarding period of Hank Mobley’s career.

An excellent analysis of Mobley’s career - I think he always delivers the goods and I’m happy to have gotten his last 3 Blue Notes in the LT series but also happy to for the Tone Poets knowing that will lead to more recognition of this period.